12,000 Rain Gardens

by: Stewardship Partners Posted on: August 08, 2011

By Stacey Gianas and David Burger

Editor’s Note: In this world we are often confronted with the challenge of how to make a difference. One of many answers to this question is to make changes to the way we live. We recycle, we eat ethically grown food, we bike. While these individual, isolated actions are beneficial, they are most often only world changing if they are done in common with other people, if they are organized. Written by Stewardship Partners, this article entitled “12,000 Rain Gardens” advocates for the spread and collective adoption of such a practice. Stewardship Partners promote the installation of rain gardens throughout Puget Sound to defend our common interest in the watershed. While the long term health of Puget Sound will require a robust and comprehensive approach, we believe that the virtue of rain gardens, especially when communally adopted, is undeniable.

Stormwater pollution is the leading threat to the health of Puget Sound and rain gardens are one of the most efficient solutions available to individual homeowners or property managers to combat the problem.

Stormwater starts as rain that picks up pollutants from hard surfaces like roads, driveways, and rooftops before flowing into storm drains. What many citizens don’t realize is that this polluted water enters local waterways untreated; whatever goes into the storm drain empties straight into the closest creek or stream. Typical pollutants from roads and driveways include oil and heavy metals from our cars. Every time we hit the brakes, dust from copper brake linings sprinkles onto the road. Even our roof materials contain zinc and copper, which are safe for people and plants, but dangerous to aquatic wildlife. Lawn care products, like fertilizers, pesticides, and moss killers are other common pollutants. When relatively harmless chemicals combine with others to form toxic mixtures, small concentrations can be hazardous to species such as salmon. The good news is that rain gardens can help absorb, filter and breakdown the bulk of these pollutants before they damage the environment.

What’s a rain garden? In brief, it’s a shallow depression filled with compost-amended soil, planted with native plants and grasses, and installed in the landscape where it can best absorb rainwater from roofs, driveways, walkways, and compacted lawn areas. If strategically placed, rain gardens can tackle polluted runoff problems in industrial settings, parking lots, and roadsides.

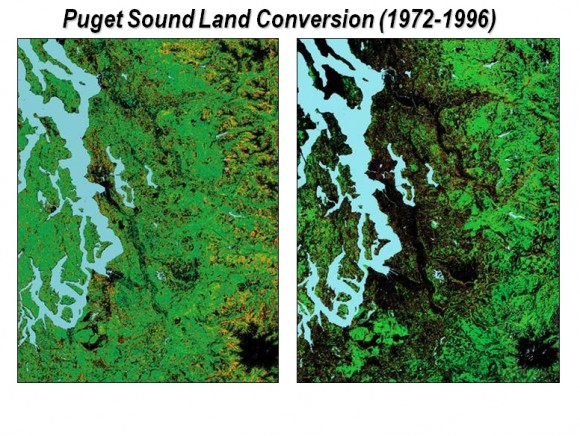

Before urban development, most rainwater would soak into the ground or evaporate from tree leaves back into the air. As paved surfaces and rooftops replace forests, we lose our natural sponges and filters. The result is creek and stream flooding, erosion, pollution and rising stream temperatures.

Imagine a rain garden as a miniature forest; plant roots and amended soils soak up and break down pollutants. Water is allowed to soak into the ground, where it cools down and slowly recharges groundwater supplies to promote more consistent water levels during the dry season, benefiting, among other things, spawning salmon. Unfortunately, this is not the fate of the majority of our stormwater, yet.

In some areas, stormwater is combined with sewage and taken to a treatment plant. While this may seem ideal for water quality, these systems are often overwhelmed by heavy rain events. When the pipes are too small to accommodate all of the water in a large storm, raw sewage combined with stormwater overflows into local waterways, resulting in combined sewage overflow. Rain gardens help take pressure off of these systems, preventing combined sewage overflows and reducing the associated fecal coliform pollution.

To save money on expensive stormwater infrastructure intended to prevent combined sewage overflows, several cities offer financial incentives for residential rain gardens. For example, the City of Seattle has invested in the RainWise program to build more rain gardens in Ballard neighborhoods. Raw sewage overflows into Ballard streams up to 40 times each year, greatly exceeding the maximum of one overflow allowed by the Federal Government. Rain garden incentives are also available in other jurisdictions including Puyallup, Bellingham, and Kitsap County. Beyond water quality improvements, these programs also beautify neighborhoods, provide habitat for birds and butterflies, and save taxpayer money. For example, when planning their Venema project in 2006, the City of Seattle estimated that investing in natural drainage would cost half as much as traditional infrastructure (4-6 million dollars compared to 9-11 million dollars).

Neighborhood rain garden clusters start with one champion who contacts their neighbors. For example, Stephanie Berg rallied her community to address drainage issues in her Burien neighborhood just south of Seattle. She was able to convince six other neighbors that the gardens look great and also serve many beneficial functions. “Beyond solving a flooding problem, it’s rewarding to know that I’m helping to protect our local stream and Puget Sound.”

Rain gardens are simple to create but must be built carefully. Garden designers must measure how quickly water drains through their soil, how much roof area contributes water to the garden, and ensure that water enters and exits the garden safely.

Stewardship Partners and Washington State University Extension are promoting 12,000 rain gardens built throughout Puget Sound by 2016. You can get involved by attending a free rain garden workshop, a volunteer planting event, or a walking tour in many cities around the Sound. Watch WSU’s 30-minute online video from the comfort of your own home, or even become a Rain Garden Mentor through WSU’s Master Gardener program. Learn more at www.12000raingardens.org.

Articles On Flora

Flora: Flora

- Apr 1 Big or Small: Who Will Grow Washington’s Cannabis Crop?

- Jul 19 A Case to Protect Public Land

- Apr 6 Oregon is a Desert State

- Dec 14 Forest Protection-The Olympic Peninsula

- Nov 30 Keeping Working Forests on the Landscape

- Nov 2 It’s a Wild Life – Can You Spare Some Passion?

- Sep 28 West Hylebos Wetlands: A Place Worth Preserving

- Aug 8 12,000 Rain Gardens

- Jul 11 Investing in Seed Banks

- Oct 21 Native Plant Spotlight: Oregon Grape

- Oct 21 Washington’s Roadless Forests