Can City Planning Make Us Cooler, Healthier and Friendlier?

by: Rex Burkholder, Portland Metro Councilor Posted on: June 17, 2012

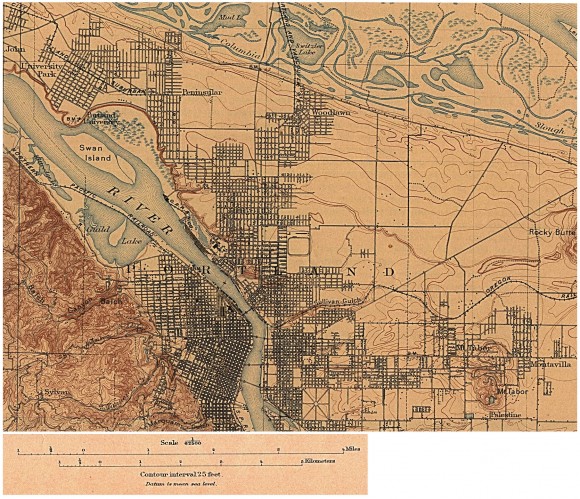

Photo: U.S. Geological Survey: 1897 Map of Portland, OR

By Rex Burkholder, Councilor, Metro regional government, Portland, Oregon

Editor’s Note: We are pleased to have Rex Burkholder tell us of the history and current efforts of Portland’s successful experiment in city planning. Portland provides us a great example of the power localities have when tackling global challenges.

“A generation ago, Portland’s metropolitan-wide planning approaches were considered ‘experimental.’ As America changes and as lessons from Portland’s ‘experiment’ emerge it is becoming increasingly evident that metropolitan Portland’s governance structure, civic engagement processes, planning approaches, and community health innovations are a harbinger for sustainable metropolitan development.”

-Arthur C. Nelson, Presidential Professor of City & Metropolitan Planning at the University of Utah

The American landscape, with its warts and astounding economic dynamism, is the product of the ideas of city planners of 100 years ago. These planners were faced with critical public health issues ranging from polluted air and water, squalid and crowded living conditions that encouraged the spread of diseases like tuberculosis and typhus, and a countryside that offered cheap, easily developable land. Zoning was adopted to separate noxious industries from residences and streetcar lines. Highways were then built to open up new areas for development. Life got better, people got healthier and the American economy thrived on building houses, cars and suburbs.

But there can be too much of a good thing (another donut, anyone?). By the 1960s, it was clear that there were unintended consequences to city building that emphasized single-family homes distant from jobs and shopping. Sprawl became problematic, causing environmental harm and increasingly seen as impoverishing culture and diminishing community life. In 1971, Oregon farmers and foresters joined forces to protect their resource base, helping push through the nation’s first comprehensive, statewide land use planning system, including the controversial and novel idea of drawing growth boundaries around cities to redirect growth inwards and severely limit rural development. The Portland metropolitan area drew a single growth boundary around its twenty four adjacent cities and created a regional government (Metro) to oversee this boundary as well as to develop and implement a 50-year vision: the 2040 Plan.

The 2040 Plan was adopted in 1995 and shares many of the goals of early planners, still targeting clean air and water, safety, health and prosperity. But we now have new challenges: global warming, globalization of the economy, an aging population and fiscal crises that cripple local, state and national government.

It’s been 50 years since Oregon adopted its land use planning system and 17 years since the 2040 plan came into being: Has setting limits on rural development and focusing development inward worked? Lets look at the results of this experiment.

Compared with similar metropolitan areas (around 2 million residents, western US, most of its growth since the 1960s), the Portland region has consumed less land per capita, has higher transit ridership and its residents drive less. In addition, most of the 24 cities in the Portland metropolitan area have seen a reversal of urban abandonment, with revitalization occurring not just in the inner city but in thriving suburbs such as Hillsboro and Gresham. A thirty-year effort to build a light rail system connecting regional centers is the foundation of a robust transit system that supports compact, mixed-use development. Ranked as the 23rd largest metropolitan area, transit use ranks 13th in the country.

In addition, high investments in biking and walking infrastructure as well as natural area protection results in a green region where more people ride bikes than any other major metro area in North America.

The combination of providing real transportation options along with a requirement that multi-family housing make up 50% of every city and county’s growth means that the combined cost of housing and transportation is lower than most other west coast regions, despite the restriction on sprawl. Being able to live without a car, or with only one, makes the difference between being able to afford to live in a desirable area or not. By one measure of poverty concentration, the Portland region is one of the least segregated by income in the country. Add to this the right of homeowners to add an accessory dwelling unit to their land; a rapidly growing population has been accommodated without the skyrocketing housing prices of a San Francisco or Seattle. There has been some displacement of lower income people as areas formerly cheap because they were undesirable (due to disinvestment, high crime rates and deliberate efforts during the 1960s to depopulate them—“urban renewal”) have been reclaimed. One of the challenges remaining is to enhance access to jobs and opportunity in those areas where lower income people live today.

It is estimated that each year, Portland area residents save $1.7 billion because they don’t drive as far as compared to typical western cities (about 4 miles less per person per day). That’s $1.7 billion that stays in the local economy instead of being spent on imported petroleum.

Portland’s reputation as a leader in sustainability includes success in limiting the growth of greenhouse gas emissions. In 1993, the City of Portland became the first local government in the United States to adopt a plan to reduce carbon emissions. In 2001, Multnomah County joined the City of Portland to adopt a joint plan—the Local Action Plan on Global Warming—that set a goal of reducing carbon emissions to 10 percent below 1990 levels by 2010. Actual per capita emissions have fallen 20% since 1993 and, even with considerable population growth, total emissions are 2% below 1990 levels.

Metro, the regional government, adopted similar goals in 2008 and has been leading regional efforts to adopt policies and actions to achieve these reductions: including land use and transportation changes, increased recycling of wastes and protection of natural areas. Metro is currently in the process of analyzing and developing a land use and transportation investment scenario that will achieve a 20% drop in greenhouse gas emissions from light duty vehicles—cars and vans—by 2020.

Conclusion: Cities are no more than complex systems for moving, producing and facilitating consumption of the stuff of life. Well-designed cities are more efficient and produce less waste, including greenhouse gases. Better design can increase social/commercial interactions and activities, as well as conviviality and employment. Living in a well-designed, efficient city like Portland is also more affordable, healthier and richer in culture and community.

1 Metro. ‘The 2040 Growth Concept.’ http://www.oregonmetro.gov/index.cfm/go/by.web/id=29882. Accessed February 14, 2012.

2 An almost miraculous turnaround in itself, until one realizes the enormous amount of citizen activism, investment in infrastructure, gang enforcement and deliberate policies it took to fight the national tide of anti-urbanism.

3 http://trimet.org/pdfs/publications/Livable-Portland.pdf was created for the 2010 Rail~Volution conference held in Portland and is a great overview of the history of the “Portland Story” and the roles of various agencies and activities.

4 “Despite having the same expenditures as the average household in the western states, the average Portland-area household spends 7 percent less on transportation annually.2 The average daily commute for a Portland area resident is 20.3 miles, four miles below the national average, and one recent study [2007] by economist Joe Cortright estimated that the resulting savings in time, gasoline, and maintenance costs amount to a total of $2.6 billion per year.3 This money has a value far beyond what the dollar amount would suggest. Since the Portland area does not manufacture cars nor refine petroleum, and residents purchase 10 percent less gasoline than the national average, roughly $800 million dollars that would otherwise leave the region each year stay in the local economy, stimulating businesses.

5 http://www.portlandonline.com/bps/index.cfm?c=49989&a=327050

6 Metro. January 2012. ‘The Climate Smart Communities Scenarios Project Phase 1 Findings Report: Understanding our Land Use and Transportation Choices.’ Page 10. http://rim.oregonmetro.gov/webdrawer/rec/231744/view/ Planning and Development – Regional Tran~g Our Land Use and Transportation Choices – Phase 1 Findings – January 12, 2012.PDF. Accessed February 2012.

Other resources:

Portland Pulse: an interactive source of data on the four county metropolitan region (including Clark County, WA) http://www.portlandpulse.org

The Portland Edge: Challenges And Successes In Growing Communities. Connie Ozawa (Editor) A collection of essays from Portland State University’s College of Urban and Public Affairs faculty.

Metro: http://www.oregonmetro.gov

Articles On Ideas

Ideas: Lessons learned, perspectives, advice and more by and for organizers working toward a more democratic society.

- Sep 26 Education Sneak Peek

- Jun 5 US Climate Movement: Funnel Money Downward if You Want to Survive

- Jan 12 For Teachers and Citizens: How to Respond to Federal Immigration Raids

- Jan 5 How To Respond When Your (Local) Government Gets Sued By A Corporation

- Dec 8 Occupy’s Not So Invisible Work

- Dec 8 Getting Specific About What We Want

- Dec 8 National Sovereignty At Stake

- Dec 8 Lessons Learned By A Federal Enforcer

- Dec 8 Sacred Democracy-The Marriage of the Ethical and the Moral

- Dec 8 A Briefing On The State-Owned Bank of North Dakota

- Nov 8 Politicizing a Social Worker

- Nov 8 Sacred Democracy-Enlightenment and Democracy

- Oct 8 The People Know Best, Should We Listen?

- Oct 8 Sacred Democracy-Democracy: a Work in Progress

- Oct 8 Dispatches from Denmark-Ærø

- Oct 8 Protect The Local Initiative Process-Why Support WA Initiative 517

- Oct 8 Questions for a County Council Could-Be

- Sep 8 A Brief Chat about Workers’ Rights

- Sep 8 Sacred Democracy-Glimmers of Empathy in the Shadows of History

- Aug 8 Native Resilience and Interethnic Cooperation: How Natives are adapting to climate change, and helping their non-Native neighbors follow suit

- Aug 8 Imagining a New Society: Comparisons from Iceland

- Aug 8 Sacred Democracy-Rites of Nature

- Jul 8 Sacred Democracy-The Beatitudes of Fairness

- Jul 8 Speaking With a ‘Fractivist’: Data Acquisition to Federal Exemptions

- Jul 8 Selections from the Public News Service-July 2013 (Audio)

- Jul 8 How the Declaration of Independence got Hijacked

- Jun 10 A Bright Future: Creative, Passionate Students at Class Academy in Portland Participate in Read the Dirt Environmental Writing Contest

- Jun 8 (Audio): Read the Dirt’s Coverage of the 2013 Public Interest Environmental Law Conference

- Jun 8 Sacred Democracy-Living Democracy as Spiritual Practice (Or Vice Versa)

- May 8 Sacred Democracy-The Moral Blueprint

- May 8 Transforming Faith

- Feb 25 Park Rangers to the Rescue

- Feb 11 Washington’s Renewables: An Introduction

- Dec 12 Species Banks

- Nov 23 Our Slaves

- Nov 17 NW Coal Ports: Voice your concerns, voice them loud!

- Nov 13 Meditations on our Future

- Nov 4 Book: Ecoliterate: How Educators Are Cultivating Emotional, Social, and Ecological Intelligence

- Oct 14 Equity, Environmental Justice, and Industrial Pollution in Portland

- Oct 8 Cities advising Counties?

- Sep 12 Talking with Washington State Legislators-Stanford

- Aug 26 Talking with Washington State Legislators-Pollet

- Aug 21 Help! I’m being Climate Changed!

- Jul 14 Questionnaire for the authors of: THE GOLDILOCKS PLANET The 4 Billion Year Story of Earth’s Climate-Oxford University Press

- Jun 17 Can City Planning Make Us Cooler, Healthier and Friendlier?

- Jun 11 The Results-2012

- Mar 25 Making Clean Local Energy Accessible Now (Part 1)

- Mar 8 Our Right To Know

- Jan 18 PROTECT ONLINE FREEDOM—READ THE DIRT DEPENDS ON IT!

- Dec 23 Talking About Our Nuclear Hazard

- Oct 28 Why make Mt. St. Helens a National Park?

- Oct 20 The Story behind the Book, A Great Aridness: Climate Change and the Future of the American Southwest

- Jun 23 McKibben Comments on Expansion of Coal Exports at Cherry Point (Whatcom County)

- Apr 3 WASTED POWER

- Dec 20 Meet Some Environmental Consultants

- Dec 5 Using Dirt to Teach

- Oct 21 The We, The I and The Dirt

- Oct 21 Turning Pollution Into Energy

- Oct 21 Orange and Green

- Oct 21 Election 2010: Talk with a WA State Supreme Court Candidate (Wiggins)

- Oct 21 Election 2010: Talk with a WA State Supreme Court Candidate (Chief Justice Madsen)

- Oct 20 Our Dirty Web Designer (Video)