Getting Specific About What We Want

by: Rex Burkholder, Portland Metro Councilor Posted on: December 08, 2013

Editor’s Note: Rex Burkholder tells an American tale—incorporating his lessons learned as an urban planner into a broader discussion on how American communities are changing, and what we can do to create the communities we want. Of the dots connected include civic engagement, gentrification, population density and transportation.

Burkholder is a repeat Read the Dirt contributor, Former Councilor for Metro Portland, OR regional government, and co-founder of Bicycle Transportation Alliance, Coalition

It’s Not About Sprawl or Density: It’s About What Makes Us Safe, Secure, Healthy and Prosperous

The battle lines are drawn: on one side the greenies and urbanists, the other, builders and NIMBYs. Both think they have the answer to our urban ills. Communities end up deadlocked and stuck in business as usual. In a recent talk with Olympia Washington’s Vision2Action on implementing the Sustainable Thurston County Plan, I began by telling a story and reminding the audience of the values everyone shares. This essay is adapted from my talk.

I would like to begin by telling you a story. It is my story and it would be unremarkable except it has become somewhat of a cliché from an old TV show, like Mayberry RFD perhaps. But it is a true story.

I didn’t grow up on a farm, although my mother did. We lived on a quiet, tree-lined street in a small capitol city in the Midwest. Big leafy elms formed a tunnel over the boulevard to downtown. We had a ravine that began in our backyard and then ran to a creek and then a river where we would skinny dip on summer days. When the dinner bell rang we would descend like wild tribes to our respective homes.

Our house was modest: Three bedrooms and a bath for our family of seven. We three boys bunked in one room and zealously guarded our allotted closet space and dresser drawers. My dad added a shower and toilet in the basement to ease the lineup in the morning. Our street was full of kids—most families had lots of children, it was the 60s. It was always easy to get up a baseball game.

My dad drove 10 minutes from our house on SW 56th to the steel mill where he was an engineer. He would be home by 5 every day except one Friday a month because of a “Safety Committee” meeting after work. It was only years later when we found a photo of him and other guys shooting pool under elk and moose heads that he confessed the “Safety” meetings were really nights out with the guys.

My mom would feed us breakfast and shoo us off to school or out the door to play in the summer. After doing the chores we kids couldn’t, she would walk down the street to gather with other mothers over coffee or Kool-Aid, until she would have to go home to meet us after school and get dinner ready for my dad’s arrival.

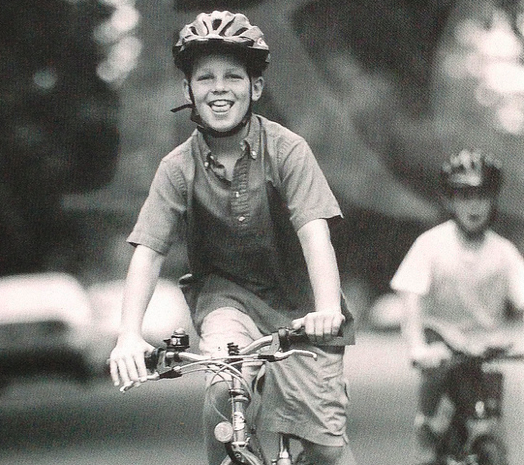

My elementary school was two doors down. Its asphalt and gravel playground kept us occupied most days until dark. My junior high school was about three blocks away. High school just a 10-minute bike ride –most kids rode bikes – at least until they were able to afford a junker car. We ice-skated at Greenwood Park in the winter, swam in the summer, and ran around in the woods and visited an Art Museum when I got older.

We never questioned our independence as kids; traffic was light, sidewalks went everywhere and there were always kids on the street wherever you went. It is both amazing and sad to hear people today talk about communities — urban communities — disparagingly as “too dense,” “crowded” and “dirty”.

The number of housing units per acre was about ten on my street, with much higher numbers along the main road to town, which had lots of three and four-story, handsome brick apartments. In addition, our big families packed a lot of people into a pretty small area.

This made for a lively, safe place to live where we knew our neighbors well. And all these people supported local businesses. Grocery stores and restaurants were just down the hill — Dunkin Donuts was my favorite stop for an apple fritter after completing my morning paper route. We would sometimes go out as a family for a 15¢ McDonald hamburger and nickel fries.

Then my dad got transferred. To Pittsburgh. A dirty old town.

Where we were going to live was really a question about perceptions of school quality. In those days that meant staying away from inner city schools in the throes of desegregation. Our family plunked down in a newer subdivision with streets named after the orchard trees that were cut down to build the houses. We still lived in a three-bedroom house and we three boys shared a room, but the house was on a street with no sidewalks, fronting an old farm-to-market road with narrow lanes, deep ditches and no place to walk or bike. There was one park in the town, a 7-11 next to the high school where everyone hung out on Friday nights and an incredible sense of isolation compared to the run-of-the-town we were used to. My older brother could drive and could get together with friends easily. Our mother became the chauffeur for us younger kids because our schoolmates lived farther away than we could safely walk. I was the only one who rode a bike to school and was regularly yelled at, pushed off the road and even hit by a full beer can. None of us went back to that town after leaving for college, joining 500,000 other ex-Pittsburgh residents who left in the last 20 years.

The discussion about sprawl versus density is really about what kind of places we want to call home, and what strategies and tools we need to create the conditions that allow us to flourish. It’s about the barriers we’ve erected in the last half-century that make it so difficult to smoothly transition to a different future. Why is it that a story like mine, that used to be a common experience, is now either mocked as nostalgia or viewed as an impossible throwback to a past that could never happen today?

Where do we want to live? Somewhere …

- That provides economic security with meaningful, dependable employment for all, so we can provide for our families.

- Where our kids are safe and independent.

- Where they enjoy growing up and will want to stay or return to as adults.

- That supports strong ties among residents, both through formal means, like PTA or citizen participation in government but also through informal means like meeting up in the park or the pub.

- That is healthy for us, having clean air and water, places to play and enjoy nature.

- That we are proud of and brag to our friends about.

We want communities where we can live a good life.

Is there a formula? We can learn from other places.

In the past 50 years we mostly achieved what we wanted and planned for:

- Our own personal parks (though mowing that lawn gets less and less fun).

- Freedom to do what we want with our “castles” (though sometimes when I’m stuck painting or plumbing instead of going out on the weekend, I question my decision to be a homeowner).

- Mobility and convenience (until too many people moved out of town and had to drive to work and now the roads are jammed).

- Quiet (until the leaf blowers and lawnmowers rev up at 7 a.m. on Saturday).

- Economic booms (and busts — the farther you live from the city center, the greater your home’s value drops each time the economy falters).

- Our piece of the pie (well, maybe not. Many people lost everything in the Great Recession).

The revolution in transportation — fueled by cheap gas, cheap cars and government subsidies for new roads, sewers and schools —revolutionized how we live, whether we wanted it or not. We got all this, and now wonder whether it was a good thing. We fled to the suburbs to find security, safety, peace and quiet and a less chaotic, more familiar community.

Did we find it? Here’s what the research tells us:

We are isolated from our neighbors – by distance, traffic-filled roads, disconnected development patterns and a lack of sidewalks and other public spaces. We often don’t know much more about our neighbors than what car they drive. Our kids suffer because they depend on us to drive them around. When both parents are at work, they are stuck.

This isolation plays out in the political world. It is much easier to see our differences than our similarities when we don’t interact with each other on a regular, informal basis. If you know the people you are arguing with, you are much more likely to see their point of view.

Suburbs are sold as good places to raise our kids, but are they healthier? Did you walk or bike to school when you were a kid? How many of your kids do? In the 1970s, over 70% of children walked or biked to school. Today that number is less than 2%. This has incredible negative effect on children’s health.

As a child, I marveled that Sears Roebuck had “husky” jeans — all my friends and family wore slim. Now almost 30% of schoolchildren are overweight and diabetes has become a childhood disease. These children will face hard futures health-wise as well as huge healthcare bills.

How about economically? Hasn’t growth and development made us richer? Lets look at this on two levels: the family (household) and society.

Urban development and housing patterns have contributed to a steady decline in our standard of living over the past 40 years. Increased housing prices, as houses became investments rather than homes, were exacerbated by the added cost of owning multiple cars necessary as sprawl destroyed viable commuting alternatives. In the early 1900s, before the automobile became ubiquitous, the average household spent about 4% of its income on transportation.

Today, the average family spends 20% of its household income on transportation. Many poorer families spend much more, with transportation often costing more than housing. About 50% of the average family’s income pays for shelter and mobility. When one is unable to live in a walkable, convenient neighborhood, their quality of life declines. Indeed, in places where urban living and urban neighborhoods are resurgent, the low-income people who used to be able to live car-free are displaced to the outer exurbs by rising housing costs.

Ouch! It seems that this revolution, like most revolutions that promise to better society, didn’t deliver.

A landscape of subdivisions, located far from workplaces, strung together by endless miles of ugly, anonymous strip development has given us anemic communities, fiscally stressed families and unhealthy people.

This is why “sprawl” has become a curse word in some circles.

Local governments are fiscally stressed as they struggle to maintain far-flung infrastructure like sewer and water pipes, roads and bridges and even schools. The American Society of Engineers gives the current condition of US Infrastructure a D- ranking because governments continue to build new infrastructure to serve new development while letting existing infrastructure crumble. Up-front costs are often hidden in a mish-mash of development fees, cross subsidies from property taxes of current residents, businesses and grants from other governments.

Yet there is a reason to hope for a better future.

Chris Nelson of the University of Utah forecasts that over 50% of housing, office buildings and shops will be new or redeveloped over the next 20 years. Think of that: we have to opportunity to shape how half of our community will look like and function. In the time span of two generations, or 40 years, almost everything in our cities and towns today will be gone or redeveloped.

What do you want to see in its place? What is worth keeping?

Remember what people really want is not a certain house design or yard size—it’s prosperity, safety, health, nature, and community.

Here’s how to design a place people want:

- Listen to people and give them what they want even if they don’t know they want it yet. In Tigard, Oregon, a fast-growing Portland suburb, was seeing lots of anger and fear from its residents. The city asked them what they wanted. They said they like their community just how it is (mostly single family with a large commercial area that attracts lots of commuter traffic) BUT wanted a Trader Joe’s grocery store to shop at and a Starbucks to congregate at. Trader Joe’s market analysis requires at least 3,000 people to live within a mile of any store location before they consider setting up shop. Only 1,000 were living around their preferred site. Armed with this information, the community did a planning process where they supported rezoning some land along main streets and in commercial areas nearby for multi-family, mixed use development, which gave them the numbers to attract a Trader Joe’s as well as giving workers options to live closer to work and commute less.

- Stop fighting the market and subsidizing losers. Many of our current zoning rules were developed to address threats that no longer exist, such as dirty industry and unsafe housing like tenements. Restrictions like separating housing and jobs, requiring lots of car parking, large lot sizes, over-zoning for single family, segregating multi-family from centers of activities, putting schools on huge sites far from homes raise the cost of living and increase how much we drive while forcing the housing industry to produce a product with a declining demand. Both older and younger households have turned away from the detached, single-family home and are looking for more convenient, smaller, more affordable housing choices. And they want to live where there is activity, restaurants and shops within walking distance.

- Recognize your future market. As a large number of boomers will soon reach retirement age, they will look for new housing options and their replacements will want to live in an exciting, lively urban environment. Will they live and commute from somewhere more exciting? Or will planners capture their drive and energy by creating places they will want to live and commit to?

- Don’t touch single-family neighborhoods. They will resist all change and will fight to the death to prevent it. Respect this and value what they offer to the City. Instead, aggressively rezone main streets and strip commercial to mixed use, allowing housing and businesses in the same area and buildings up to 4 to 6-stories tall. Lower the speeds on these streets and reduce the number and width of lanes and lane widths so these areas can become pedestrian magnets instead of car-dominated deserts.

- Forget number 4. Allow accessory dwelling units — mother in law apartments — in all zones, especially single-family neighborhoods. Being able to convert part of a large house into a rental, or rebuild the garage, has many benefits without affecting the character of the neighborhood. It makes housing affordable for new families, helps elderly stay in their neighborhoods, either through downsizing in their own home or by raising their income, and provides greater tax revenue to utilize and support public services.

- Build good public spaces. Parks, plazas, libraries and schools can spark private investment and public support for new forms of development. Think carefully about how you spend scarce public resources and make sure it contributes to a more accessible, healthy, vibrant community — especially schools.

The question isn’t sprawl or density. What kind of community do you want to create? A place that has affordable housing choices and where a 9-year-old can walk to the park or the store to buy a popsicle, by themselves. A place, where they won’t be by themselves because all their friends will be going with them, that encourages walking and cycling and people are healthier and more connected. A place that uses public dollars wisely by avoiding expensive expansions and reinvesting in its existing communities. A place that integrates home, work, school and people into a dynamic, engaged and engaging community. We have the opportunity and the knowledge to build a place we and our children are proud of.

Photo: Bicycle Transportation Alliance

Articles On Ideas

Ideas: Lessons learned, perspectives, advice and more by and for organizers working toward a more democratic society.

- Sep 26 Education Sneak Peek

- Jun 5 US Climate Movement: Funnel Money Downward if You Want to Survive

- Jan 12 For Teachers and Citizens: How to Respond to Federal Immigration Raids

- Jan 5 How To Respond When Your (Local) Government Gets Sued By A Corporation

- Dec 8 Occupy’s Not So Invisible Work

- Dec 8 Getting Specific About What We Want

- Dec 8 National Sovereignty At Stake

- Dec 8 Lessons Learned By A Federal Enforcer

- Dec 8 Sacred Democracy-The Marriage of the Ethical and the Moral

- Dec 8 A Briefing On The State-Owned Bank of North Dakota

- Nov 8 Politicizing a Social Worker

- Nov 8 Sacred Democracy-Enlightenment and Democracy

- Oct 8 The People Know Best, Should We Listen?

- Oct 8 Sacred Democracy-Democracy: a Work in Progress

- Oct 8 Dispatches from Denmark-Ærø

- Oct 8 Protect The Local Initiative Process-Why Support WA Initiative 517

- Oct 8 Questions for a County Council Could-Be

- Sep 8 A Brief Chat about Workers’ Rights

- Sep 8 Sacred Democracy-Glimmers of Empathy in the Shadows of History

- Aug 8 Native Resilience and Interethnic Cooperation: How Natives are adapting to climate change, and helping their non-Native neighbors follow suit

- Aug 8 Imagining a New Society: Comparisons from Iceland

- Aug 8 Sacred Democracy-Rites of Nature

- Jul 8 Sacred Democracy-The Beatitudes of Fairness

- Jul 8 Speaking With a ‘Fractivist’: Data Acquisition to Federal Exemptions

- Jul 8 Selections from the Public News Service-July 2013 (Audio)

- Jul 8 How the Declaration of Independence got Hijacked

- Jun 10 A Bright Future: Creative, Passionate Students at Class Academy in Portland Participate in Read the Dirt Environmental Writing Contest

- Jun 8 (Audio): Read the Dirt’s Coverage of the 2013 Public Interest Environmental Law Conference

- Jun 8 Sacred Democracy-Living Democracy as Spiritual Practice (Or Vice Versa)

- May 8 Sacred Democracy-The Moral Blueprint

- May 8 Transforming Faith

- Feb 25 Park Rangers to the Rescue

- Feb 11 Washington’s Renewables: An Introduction

- Dec 12 Species Banks

- Nov 23 Our Slaves

- Nov 17 NW Coal Ports: Voice your concerns, voice them loud!

- Nov 13 Meditations on our Future

- Nov 4 Book: Ecoliterate: How Educators Are Cultivating Emotional, Social, and Ecological Intelligence

- Oct 14 Equity, Environmental Justice, and Industrial Pollution in Portland

- Oct 8 Cities advising Counties?

- Sep 12 Talking with Washington State Legislators-Stanford

- Aug 26 Talking with Washington State Legislators-Pollet

- Aug 21 Help! I’m being Climate Changed!

- Jul 14 Questionnaire for the authors of: THE GOLDILOCKS PLANET The 4 Billion Year Story of Earth’s Climate-Oxford University Press

- Jun 17 Can City Planning Make Us Cooler, Healthier and Friendlier?

- Jun 11 The Results-2012

- Mar 25 Making Clean Local Energy Accessible Now (Part 1)

- Mar 8 Our Right To Know

- Jan 18 PROTECT ONLINE FREEDOM—READ THE DIRT DEPENDS ON IT!

- Dec 23 Talking About Our Nuclear Hazard

- Oct 28 Why make Mt. St. Helens a National Park?

- Oct 20 The Story behind the Book, A Great Aridness: Climate Change and the Future of the American Southwest

- Jun 23 McKibben Comments on Expansion of Coal Exports at Cherry Point (Whatcom County)

- Apr 3 WASTED POWER

- Dec 20 Meet Some Environmental Consultants

- Dec 5 Using Dirt to Teach

- Oct 21 The We, The I and The Dirt

- Oct 21 Turning Pollution Into Energy

- Oct 21 Orange and Green

- Oct 21 Election 2010: Talk with a WA State Supreme Court Candidate (Wiggins)

- Oct 21 Election 2010: Talk with a WA State Supreme Court Candidate (Chief Justice Madsen)

- Oct 20 Our Dirty Web Designer (Video)