Crown Heights Tenant Union: Building Power One Building at a Time in NYC

by: Simon Davis-Cohen Posted on: May 25, 2016

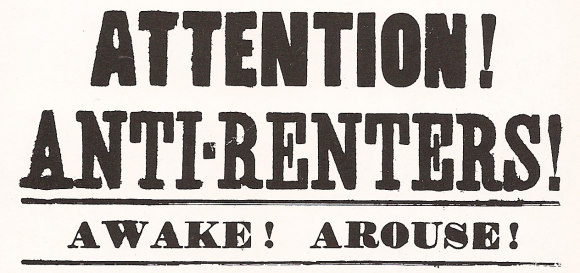

Editor’s Note: Longtime New York City tenants have been getting evicted and displaced in neighborhood after neighborhood in recent years. Harlem, the Lower East Side, Williamsburg, Bushwick, South Bronx, Park Slope, Flatbush, Crown Heights, etc.—rising rents are ubiquitous and affordable housing endangered, to say the least. Tenants have been defiant; they have protested, written op-eds, attended regulatory hearings and risked arrest, but have struggled to find an effective organizing strategy that gives them collective power to fight back against landlords. The conditions are stacked against them. They face multinational corporations, city and state governments with close ties to the lucrative real estate market, a void of community decision-making power, and divide and conquer tactics.

That’s why the Crown Heights Tenant Union has generated the attention it has. Emerging from an alliance between Occupy activists, longtime Black Brooklyn tenants, labor and tenant organizers in 2012, it offers an innovative response to the circumstances all New York City tenants face.

Simon Davis-Cohen sat down with Union member Joel Feingold to discuss the inner workings, lessons learned, history, tactics and mentality of the Union, state preemption, and more. Read the full interview below.

This interview was reviewed and approved by the Crown Heights Tenant Union’s Organizing Committee.

This piece was originally published on Indypendent.org.

Can you give us some basic background on the CHTU? When did it start, how? Is it the progeny of a previous group?

The first source of the Crown Heights Tenant Union was the Crown Heights Assembly, which was a spur of Occupy Wall Street. After Occupy, people wanted to organize with Black working class tenants in Crown Heights, around whatever issues they wanted to work on. A housing campaign targeting a brokerage called MySpace Realty emerged from that. MySpace is implicated in a lot of displacement and rent overcharge in the neighborhood.

The core simple demand of that campaign was that MySpace disclose all rent histories to prospective tenants, and that they only rent apartments at the legal rent. These were really simple, basic demands that we thought we could win quickly to build power and a base. But MySpace sued us for $31 million for defamation, conspiracy and sabotage. Thanks to pro-bono movement attorneys at Rankin and Taylor, we got the lawsuit thrown out without a judgement. But in the course of doing this work tenants started saying that we needed to be focusing on the immediate displacement, repair and overcharge issues—about, really, the social and ethnic cleansing of the neighborhood, immediately.

So, from that campaign we decided that we needed to transition to a new model.

The second source of the union was the tenants who were involved. A lot of them were long-term Black tenants and working class tenants who had a lot of experience with New York’s and Brooklyn’s labor movement. SEIU Local 1199, the Hotel Trades Council, other groups—a lot of the people who were a part of the Crown Heights Assembly also came from a radical labor background. That is how we came up with the direct action and collective bargaining thrust of the Crown Heights Tenant Union.

The third source came early in the planning stages of the union. We were approached by the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board (UHAB)—a tenants rights organization that supports low-income housing co-ops in the city. UHAB goes back to the 1970s, and squatting in the Lower East Side. UHAB has played a central role in organizing existing and new tenants associations and bringing them into the CHTU.

What does the CHTU consist of today? How many buildings are unionized?

At this point there are 60 to 70 buildings that have tenant associations affiliated with the tenants union. The union structure is three fold. At the base are the autonomous associations of tenants in a building. The second level are the Locals, which are unions of tenant associations that share a common landlord. Third is the union’s General Membership Meeting. In between all three is the Organizing Committee, which is where representatives from the associations and locals democratically write the agenda for the General Membership Meeting. At the meeting is where we discuss new proposals for actions and strategic questions—everything has to be approved by the General Membership Meeting, including this interview.

What are some decisions that have come out of those strategic conversations?

We were very deeply involved in the a fight over New York City’s rent laws that took place in Summer 2015. As the rent laws are governed primarily by the state legislature, we participated in major actions at the state capitol: blockading the entrance to the governor’s office; demanding a repeal of the neoliberal pro-landlord provisions that were written into the rent laws in the 1990s and the last decade—things like the 20% eviction bonus and preferential rent. We were demanding new rights, and tenant union contract demands at the state level.

But our core strategy is to target our landlords directly to demand new rights. Things like improving equality of repairs between new and old tenants and a five year rent freeze, which has been a core demand since the beginning. We target our landlords with direct action by picketing outside their office, we’ll go to their homes and picket there, we’ll go to their banks to picket there. We’ll march through the streets calling on tenants to join us. We march on store fronts that these landlords hold hostage to rent to high end bars and boutiques, which we see as a form of colonialism. We’ll target landlords that are doing eviction by jackhammer—intentionally destructive repairs or needless noise to drive tenants out. We emphasize our need for new rights by way of collective bargaining agreements—tenant union contracts—and demand that those rights be written into law. All of these are tactics that have emerged from the multiple levels of the organization.

How is Crown Heights a hostile place for tenants and tenant organizers?

One: obviously we’re up against huge market forces. Predatory equity; Wall Street-backed landlords, corporate landlords, multinational landlords like Akelius, multibillion dollar pension funds. The structural impediments are huge, but we have been able to win significant victories: stopping every attempt to evict an active member of the CHTU, repairs, forcing landlords not to claim rent increases for renovations allowed under the law.

Two: Landlords use divide and conquer tactics. They pit old tenants versus new tenants, Black tenants versus non-Black tenants. They try to use the class dynamics of gentrification and displacement against us. But that is what the tenant union is designed to prevent. We use a class analysis to do this. We emphasize the importance of leadership of longterm, Black or West Indian tenants, and leadership of working class tenants. Our class analysis is that we are all tenants, and that while we are caught in a cycle of displacement and rent overcharge, displacement and overcharge are not equitable in terms of the social harm done—longterm Black and West Indian tenants are harmed most. But new tenants are overcharged. The result is the transforming of a working-class neighborhood into a citadel of the rich. We unite to try to break this cycle of exploitation. So, longterm and new tenants see each other as fellow tenants, and we fight back together.

What are a few examples of these divide and conquer tactics?

It’s material. Landlords will sometimes shower repairs on new tenants while denying heat to old tenants. At first it seems to be a barrier to solidarity, but it is not. The new tenants are being illegally overcharged, and the old tenants are being denied heat. And once people recognize that their demands are intersecting, although they are different, that’s when you can begin to build real solidarity. Not a sort of philanthropy or savior complex, but a real solidarity that is based on materiality and mutual need.

What words of advice do you have for any young tenants unions out there?

Part of it goes back to the genealogy of our coalition.

One of the early differences of opinion within the union was over how to relate to mainstream Democratic politicians who were coming to our meetings. A lot of the Occupy people were suspicious—sometimes this manifested as a divide between longterm and new tenants. Through the militancy of our demands and actions, we were able to come to a position where we now have independence from the elected officials. But politicians will come out to our demonstrations and even join us in direct action. While we didn’t feel beholden to these officials in any way, we knew that we could turn to them (but not rely on them) when we saw them yelling at landlords with us.

It was sort of a wake-up for some of the Occupy kids—to really grapple with what it means to organize with a Black neighborhood where the 100 year struggle for the vote is such a core part of its political history. This is not an incidental part of the politics of Black America. To really grapple with that question I think was really important for us to understand that while we need to have this vision of independent working class politics—Black-led politics—there is a real political structure that has been built up during years of struggle that we need to be aware of.

And of course, Crown Heights has a really divers intra-Black community. You have West Indian radicals that want nothing to with the Democratic Party too.

Before 1971, New York City had the power to regulate rent locally. Now, thanks to state preemption, that authority now lies at the state capitol. How does this impact your work? Does it?

Preemption creates a Governor-Mayor, State-City power battle. It creates this situation where the governor and mayor can sort of pass the puck of responsibility back and forth. So it creates two targets for our activism, which can be beneficial. We can win things like the Tenant Protection Unit at the state level, and at the New York City level we can use enforcement mechanisms like the Alternative Enforcement Program at the City’s department of Housing and Preservation. So there are number of avenues for us to pursue indirect legal leverage over these landlords through these various state and city agencies.

But preemption complicates things. Because of preemption the rent laws are in the hands of the upstate Republican machine as opposed to the downstate Democratic machine, which makes things a lot harder—though again, these two machines can pass the puck to prevent any change, as the main currents of both parties are anti-tenant and pro-landlord. Certainly in the 2015 battle over the rent laws, we had no power of constituency over a lot of the people making the laws in the state legislature. Many politicians at the capitol—including Governor Cuomo—are in the pockets of the real estate industry. It’s really a problem of the neoliberal consensus.

Would your advice to a young tenants unions change if they were organizing in a non-preempted town or city?

Yes. If there was more local control over the rent laws in New York we’d have a much better chance of winning some of our demands like the repeal the 20% eviction bonus, because since Occupy we’ve started to build a really robust movement that unites the labor and tenant movements. And that organizing has started to be reflected in local politics—it has also run up against the Democratic machine and the non-profits’ mechanisms for co-optation.

But I don’t know that preemption is the core issue. It is about the landlords and their power. Though, if there were more local control, we would be in a better position to have better rent laws. But our tactic is to work to win new tenant rights from our landlords directly, through direct action—pickets, rent strikes, targeting their banks, taking over their office lobbies, rallying outside their houses—to win collective bargaining agreements. Then we’ll turn around to the state, or the city—both—to demand that the new rights be written into law to make them universal.

More local control over the rent laws would be good. It would help us do that more quickly. But it’s not the silver bullet.

Photo: Wikimedia

Articles On PRESS

PRESS:

- Jun 13 The Fight For Local Democracy in New York City

- May 25 Crown Heights Tenant Union: Building Power One Building at a Time in NYC

- May 25 Activists Occupy Shipping Container to Halt AIM Pipeline Construction in Upstate NY

- May 25 Barrington, NH votes 795 to 759 to Adopt Community Bill of Rights to Protect Waterways

- May 25 Revoking The Consent to be Governed

- Apr 25 Announcement of Nationally Coordinated Prisoner Workstoppage for Sept 9, 2016

- Apr 19 The Spirit of Occupy Lives on in France’s Emerging Direct Democracy Movement

- Apr 19 How Sanders Could Lay the Foundation for a Third US Political Party

- Apr 10 Some Possible Ideas for Going Forward

- Apr 7 Reclaiming Black Land in Grafton, New York

- Apr 7 Meet the Lead Organizer Behind the Upcoming Mass Sit-Ins to get Money out of Politics

- Mar 28 Dismantling Corporate Control Isn’t a Spectator Sport: An Interview With Thomas Linzey

- Mar 16 Preempting Trump: Barnstead, NH Adopts First-In-Nation Law Protecting Against Religious Persecution

- Mar 4 This New Era Of Unrest

- Mar 1 Washington State Supreme Court Guts Local Ballot Initiative Process

- Feb 9 Debating A ‘New’ Pan-European Anti-Austerity Movement

- Feb 9 How New York Stopped A Liquefied Natural Gas Project In Its Tracks

- Jan 28 Food, Land, and Freedom

- Jan 27 One Oregon Tribe’s Fight for Federal Recognition

- Jan 20 Worker, Civil and Environmental Rights as Legal Ends: Defying Commerce’s Logic

- Jan 20 Fast-Food Workers Plan Wave Of Strikes For 2016 Primaries

- Jan 18 Greece’s Varoufakis to Launch Pan-European Progressive Movement

- Jan 6 California’s Largest Tribe Passes First-In-Nation Enforceable Ban On GM-Salmon and GMOs

- Dec 29 The Leap Manifesto

- Dec 29 “People’s Injunction” Launched to Block Canadian Pipelines

- Dec 29 How Black Lives Matter Came Back Stronger After White Supremacist Attacks

- Dec 29 Can Local Law Enforcement Be Democratized By A People’s Movement?

- Dec 9 Preempting Democracy: What’s Not Being Voted on This November Is Sinister

- Dec 9 A Bill of Rights That Puts Workers Above Corporations

- Dec 9 Government and Gas Industry Team Up Against Local Fracking Ban Initiatives in Ohio

- Dec 9 Fighting Fossils, Letting Go of Regulatory Law

- Aug 26 In Colorado, A Revolutionary New Coalition Stands for Community Rights

- Aug 26 Climate Crisis Pits Local Governments Against 19th-Century Legal Doctrine

- Aug 26 Hundreds of Communities Are Building Legal Blockades to Fight Big Carbon

- Jul 21 Will Labor Go Local?

- Jul 20 Challenging Bedrock Law: “Dillon’s Rule” in Detroit and Beyond

- Jul 19 Defining a Federalist Approach to Immigration Reform

- Jul 18 Why Are Fracking Hopefuls Suing a County in New Mexico?

- Dec 8 Finally, The Court Case We’ve All Been Waiting For

- Nov 8 Ohio and Colorado Voters Adopt Community Bills of Rights

- Nov 8 Community Rights Organizer Sets Sights on Fracking in Southern Illinois

- Nov 8 Critical Issues Deserve a Higher Standard

- Nov 7 Indigenous Peoples Experience Of Climate Change And Efforts To Adapt (Video)

- Oct 8 Naomi Klein Addresses New ‘Mega Union’

- Oct 8 Disco may be the only way to stop Monsanto (Video)

- Oct 8 (Ohio) Frack-Backers Launch Preemptive Strikes against Democracy Attempt to Block Community Bills of Rights from Voters

- Oct 8 The California Domestic Workers Bill of Rights Speaks to the Need for Wise Immigration Reform

- Oct 8 Support Local Food Rights Will Not Be Deterred by Legislature’s Blow to Democracy

- Oct 8 Economic Sovereignty At Stake

- Oct 8 Sangerville, Maine Adopts Community Bill Of Rights Ordinance to Reject Transportation and Distribution Corridors

- Oct 8 Sacred Headwaters

- Oct 8 Oregon Communities Launch Statewide Network for Community Rights

- Sep 8 Bowling Green, OH Group Submits Bill of Rights Petition

- Sep 8 Judgment Day

- Sep 8 Judge Blocks Envision, SMAC Initiatives from Appearing on Ballot

- Sep 8 Why a Rights Based Ordinance In Nottingham, NH?

- Aug 8 What is the Local Food System Ordinance of Lane County?

- Aug 8 Lane County Initiative to Protect Local Farming Encounters Hurdle; Campaign Still Targeting May 2014 Election

- Aug 8 Benin: Local Knowledge And Adaptation To Climate Change In Ouémé Valley, Benin

- Aug 8 Local Food System Ordinance of Lane County, Oregon

- Jul 8 Envision Spokane Statement to Legal Action to Block the Community Bill of Rights from the Ballot

- Jul 8 Why does the Spokane City Council continue to ignore and distort the substance of the Spokane Community Bill of Rights?

- Jul 8 History of Efforts to Keep the Spokane Community Bill of Rights Initiative off the Ballot

- Jul 8 East Boulder County United Launches Campaign for the Lafayette Community Rights Act to Prohibit New Oil and Gas Extraction

- Jul 8 Benton County Community Group Files Petition for the Right to a Local, Sustainable Food System

- Jul 8 Rivers and Natural Ecosystems as Rights Bearing Subjects

- Jun 8 Caring for Home through Nature’s Rights

- Jun 8 From Field to Table: Rights for Workers in the Food Supply Chain

- Jun 8 Will Ohio Be Fracking’s Radioactive Dumping Ground?

- May 7 First County in U.S. Bans Fracking and all Hydrocarbon Extraction – Mora County, NM

- May 7 Self-Replication at Stake in Monsanto Patented Seed Case

- May 7 Guatemala: Mayan K’iché Environmental Sustainability As A Way Of Life

- May 7 Small Farms Fight Back: Food And Community Self-Governance

- May 7 State College Borough Gov Denies Pipeline Permit: Fight Isn’t Over

- May 7 Muzzling Scientists is an Assault on Democracy

- Apr 8 An Addition to the Climate Movement-Civil Disobedience Toolkit

- Apr 2 Thornton, New Hampshire Rejects Community Bill of Rights To Ban Land Acquisition for Unsustainable Energy Systems

- Apr 2 Grafton, New Hampshire Adopts Community Bill of Rights That Bans Land Acquisition for Unsustainable Energy Systems

- Apr 2 Highland Township Adopts Community Bill of Rights That Bans Toxic Injection Wells

- Apr 2 PSU Pipeline Violates Community Bill of Rights

- Jun 26 The United States Conference of Mayors Resolves that Corporations are not Natural Persons etc.

- Apr 30 Information and Documents concerning Oregon LNG

- Mar 9 1st Annual Read the Dirt Writing Competition!

- Feb 24 Oil Sands Pipelines, here?

- Feb 23 PRESS: Genetically Engineered Animals?

- Feb 23 PRESS: The 9th Annual Skagit Human Rights Festival March 2012

- Jan 27 Bellingham Rights-Based Ordinance Proposed to Stop Coal Trains

- Jan 26 PRESS: Occupy Seattle Joins in Solidarity with United Farm Workers

- Jan 20 Planning For a Future (Original)

- Jan 8 PRESS: Associated Students of Western Washington University Adopt Resolution Opposing Cherry Point Coal Terminal