One Oregon Tribe’s Fight for Federal Recognition

by: Simon Davis-Cohen Posted on: January 27, 2016

Editor’s Note: This piece originally appeared on truth-out.org.

Millions of indigenous people living within US territory exist in a legal limbo – unrecognized by the US government. They enjoy none of the powers and benefits federally recognized tribes enjoy as sovereign nations.

In the continental United States, tribes whose treaties were never acknowledged or ratified are not “Indians” in the eyes of the federal government. The indigenous peoples living in US colonies and in states outside the continental United States (Hawai’i and Alaska) are left out of the US government’s definition of “Indian.” Some have populations in the hundreds of thousands while others have tiny populations due to the ravages of colonial violence. None are sovereign.

Over time, many have won recognition and now enjoy nation-to-nation relations with the US government. Some remain in the midst of decades-long legal disputes to win recognition, like the Chinook Indian Nation in Washington State. Others, including over 500,000 Native Hawaiians, are actually fighting not to be recognized by procedures they see as a continuation of federal land grab policies. At the end of the day, it is sovereignty – political control of their land – that they all pursue. There is no one-size-fits-all preference or procedure.

In fall 2015, members of one small unrecognized tribe on the Columbia River, known as the Celilo Wy’am, shared ancestral documents with Truthout showing that although they remain unrecognized, the federal government in fact recognized them in the 1950s. In doing so, they expressed their hope that this sharing of their documents and stories will help their years-long struggle to gain some semblance of sovereignty.

Nonexistent in the Eyes of the Law

Lana Jack is one of the roughly 20 remaining Celilo Wy’am people of the Columbia River’s historic Celilo Falls. She inherited her ancestral name, Huy-ux-pul, from her grandmother; it translates as “The Ever-Present Cooling Mist of the Falls.” But the falls, once called the “Wall Street” of the Northwest, an epicenter of indigenous cooperation and commerce, are today silent, drowned by the colossal Dalles Dam built in 1957. And the tribe that has lived at the falls for an unfathomable 10,000 years, according to most estimates, remains federally unrecognized.

The Jack family – one of the tribe’s last standing families – embodies the hypocrisy.

Lana Jack lives in the “New Celilo Village,” a US Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA)/Army Corps of Engineers homage to the original village. New Celilo, windswept and poorly maintained by its federal overseers, consists of a cul-de-sac on the side of Oregon’s I-84. To get to the river you must cross a BNSF railroad, then follow an underpass beneath the interstate to the river’s shore. On a hill, just out of sight from New Celilo, overlooking the Columbia Gorge, lies the Wy’am’s relocated burial site.

On the sage-spotted hillside lie many of Jack’s ancestors, including Minnie Showaway, her great-grandmother, a Wy’am leader and year-round resident of the original village, whose allotment Jack inherited from Jack’s uncle – Minnie’s son – Moses Showaway. But because Jack is not an “Indian” in the eyes of the US government, the BIA and Army Corps of Engineers tried to evict her in 2007 when they made renovations to Celilo Village’s infrastructure to honor the 50-year anniversary of the flooding of the falls.

The BIA told her she had no rights to the land, and gave her 90 days to vacate. Also ironically, that same year, the Oregon State Senate issued a joint memorial acknowledging that the “[Wy’am] remain there [in Celilo Village] despite repeated attempts of the United States to remove them from their home.”

“We have survived six relocation plans,” Jack told Truthout. “With the integrity of our ancestors intact.”

Though the Celilo Falls are a regional heritage, the indigenous people of the falls – the Wy’am – are legally treated as though they do not exist. “In the eyes of the US government and the State of Oregon, I am not an Indian,” Jack said. “But as an heir from the original village, I have aboriginal title.”

Their case is rare, an asterisk in federal Indian law. As The Oregonian wrote in 2007: “Some law experts consider Celilo [Village] the most complicated piece of land in Indian Country.”

In the midst of bloodshed – as settlers and indigenous groups were at war on the Columbia – the governor of the Washington Territory, Isaac Stevens, convened chiefs from along the Columbia River, including Yakima, Nez Perce, Umatilla, Warm Springs and others. Those meetings resulted in the Wasco Treaty of 1855.

“We want you to agree to live on tracts of land,” he said in federal government minutes of the Treaty Council. “We want you to sell the land you do not need to your Great Father [the President of the United States]…. you will be doctors and lawyers like white men.”

The treaty resulted in four Native American reservations; one each for the Yakima, Nez Perce, Umatilla and Warm Springs, the only federally recognized tribes with treaty fishing rights on the Columbia. But one chief objected: “You want us to go there [to a reservation]. What can we think of that? … Your words since you came here have been crooked.”

And after the reservation borders were disputed, US Army Gen. Joel Palmer, a pioneer of the Oregon Territory, announced, “We did not come here to talk like boys…. which will you do, take that line or have it all thrown away?”

So it is no surprise that at the time the treaty was to be signed, several chiefs from the Dalles area “who were in attendance during the first days of the Council,” according to the minutes, “had returned home to catch their usual supply of Salmon.” One chief in attendance, Kamiakin of the Palouse, assured Governor Stevens that these tribes “would sign the treaty” if the governor “thought it necessary.” But the chiefs were never asked.

One Celilo Wy’am chief stayed to sign, though, with a defiant “X.” Among Columbia River indigenous peoples “X” is a sign of danger and warning on a path or trail. “My ancestors told me to remember that he signed in protest,” Jack said.

The Wy’am are among the defiant tribes who would not remove themselves onto reservations. Their land at the falls – now New Celilo Village – was designated an “off-reservation” fishing site for the recognized tribes. Yet because the Wy’am themselves are not recognized, they have no fishing rights of their own.

Lana Jack’s brother Leon and sister Lila, both Wy’am and not enrolled in any federally recognized tribe, face charges for illegal fishing on the Columbia.

According to the Hood River Circuit Court, Lila Jack was cited for two fishing-related offenses on September 11, 2015. Her case has been taken over by a private law firm Morris, Smith, Starns & Sullivan, PC. According to both of Lila’s sisters, her attorney has advised her not to speak about the case publicly. Her attorney also declined to speak with Truthout.

Leah, the third Jack sister and a librarian at Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission’s StreamNet Library in northeast Portland, told Truthout, “Lila has been fishing all these years. It just took one person to say ‘you’re not enrolled.'” She added, “These strong-armed tactics by the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Enforcement are getting more prevalent. They are moving in a direction that’s not helpful. Some of the things they are doing are not in line with why they were formed.” The fish enforcement body is the policing arm of the fish commission – created by the four federally recognized Columbia River tribes in 1977 to help the tribes manage the river and their fishing rights. Now, however, the fish commission increasingly competes with the tribes for settlement money from the federal government.

In 2015, Oregon granted the fish enforcement organization permanent authority to enforce state laws, rather than just the tribal laws to which it was once confined. These powers, according to Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Enforcement’s Mich Hicks, allowed them to cite Lila – who is considered a “non-Indian.”

Leon’s 2009 case is still open. Leon told Truthout over the phone that he will continue to fish. “Let them arrest me,” he said.”These are my ancestral fishing holes.”

Lana says she does not fish, but her lack of federal recognition nevertheless creates daily contradictions in her life. She lives on designated Native American land managed by the BIA. Yet, the BIA only has jurisdiction over federally recognized indigenous peoples.

Though she is unrecognized, the BIA still comes into her home for inspections.

Stanley M. Speaks, the BIA’s Northwest regional director, told Truthout, “She’s probably about the only one that fits into this situation … you have to be one of those that have family members of the original families on the site. But,” he added, “there wouldn’t be very many of those.”

Shifting Terms of Legal Recognition

The Jacks and the Wy’am have a strong legal case to receive recognition.

According to documents provided by Lana Jack, when Minnie Showaway was granted the .47-acre “public domain allotment” that Jack inherited, she was recognized by the US Congress as a member of one of “those permanent resident Indian families” of the original village. These “individual Indians not enrolled in any recognized tribe,” wrote Congress in 1955, two years before the flooding, “who through domicile at or in the immediate vicinity of the reservoir … have an equitable interest in the fishery.” Though unrecognized, the permanent families were given fishing rights.

Additionally, in the minutes of the 1855 Treaty Council, Stevens also promised “all the Bands of the Columbia below the Walla Walla down to White Salmon River … fishing stations.” This encompasses Celilo and the Wy’am.

Despite this, Leon, Lila and the rest of the Wy’am people enjoy no such rights to their ancestral fishing grounds today. The federal government has gone back on its word.

When the BIA was trying to evict Lana in 2007 it argued in its eviction notice that the .47-acre allotment “was already in trust for the [recognized] tribes and other Columbia River Indians.” It “was never taken into trust” for Jack’s ancestors, the eviction notice said. “While it is unfortunate that the BIA represented to [Jack’s ancestors] that it would take the land … into trust for them individually [and their heirs] the BIA cannot now rectify the matter.”

In order to have rights to BIA-controlled land and rights to fish on ancestral waters, you have to be a recognized “Indian.” But rather than fix this hypocrisy by recognizing the Wy’am, the BIA has instead moved to remove those land and fishing rights.

“It is a continuation of the genocide of my ancestors,” Jack said. “They tried to kick me out of Celilo Village based on [an argument that] I’m not an Indian.”

She fought the eviction and won but she did not set a legal precedent. She says the BIA, the Army Corps of Engineers and even her attorneys pressured her into signing an out of court – non-precedent-setting – settlement.

In that settlement, Jack finally got some recognition. “Lana Jack,” the settlement reads, “is a Wyam Indian.” She is “one of the ‘other Columbia River Indians … in the vicinity of Celilo Falls.'” For the first time since 1955, a Celilo Wy’am Native American was recognized by the US government. This is the first time any mention of her settlement has been published.

Spreading Awareness About the Celilo Wy’am

Lana Jack is bringing this story to the world.

Recently, her work to mobilize donations for impoverished Native Americans along the Columbia River was featured on the cover of the local Dalles Chronicle; she has spoken out publicly in support of the Lummi Nation’s resistance to fossil fuel infrastructure; and Hood River, Oregon’s mayor Paul Blackburn publicly apologized for the genocide to Lana and Lila Jack on Oregon’s first annual Indigenous Peoples Day in October 2015.

And Lana Jack has garnered the support of two Yakima chiefs.

“The generational trauma that has come to the women of our family has been devastating. It has taken many of us prematurely,” Jack said.”I am living with symptoms of the trauma that comes with genocide.” Sometimes, she says, she gets so tired.

“When the salmon are all gone,” she said, “we are supposed to go. Be gone.” But despite the Columbia’s many dams and the warming waters, there are still salmon swimming in the river. And though the falls are under water, their mist remains – ever-present in the minds of the Columbia’s many tribes.

Jack is making it hard for the public and US government to ignore the hypocrisy of the system under which she lives. “We want them to authorize our existence,” she said.

Jack is treated like an “Indian” under the BIA’s jurisdiction. Her home is inspected like her federally recognized neighbors’ homes. But she and her family remain ineligible to receive reparations and have no fishing rights.

Stanley M. Speaks from the BIA reacted dismissively when asked about Lana Jack’s situation. “At least we’re keeping the street up, and maintaining the well system and making sure there is good water and a sewer system for her,” he told Truthout. “I think she ought to be pleased that we’re doing it, and not be bitching and complaining about it.”

Leah Jack says that in the face of such dismissiveness, her family will continue its struggle. “We were taught to stand and fight – that is what Lana is going to do,” she said. “She will stand. Some people see that as combative, but she’s just calling people on their BS. They don’t want to talk about what’s really going on, and that’s genocide.”

Featured photo: Lana Jack above the Celilo Wy’am’s original burial site, January, 2016. (Simon Davis-Cohen)

Photo 2: Lana Jack with her dog, above the Celilo Wy’am’s original burial site: now underwater, drowned by the Dalles Dam, January, 2016. (Simon Davis-Cohen)

Photo 3: Lana Jack at the Celilo Wy’am’s relocated burial site, on a hill above the drowned Celilo Falls. Jack points to the grave of a recent ancestor, January, 2016. (Simon Davis-Cohen)

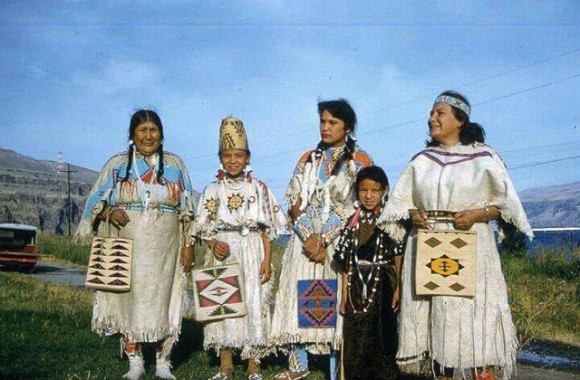

Photo 4: Relatives of the Jack siblings, on the shores of the Columbia. From left to right (with relations to the Jack siblings in parenthesis): Minnie Wesley Showaway (great grandmother), Irene Brunoe (aunt), Mary Cook Jack (mother), Estella Lawson Brunoe (aunt), Irene Williams Brunoe (grandmother). 1958. (Courtesy of Lana Jack)

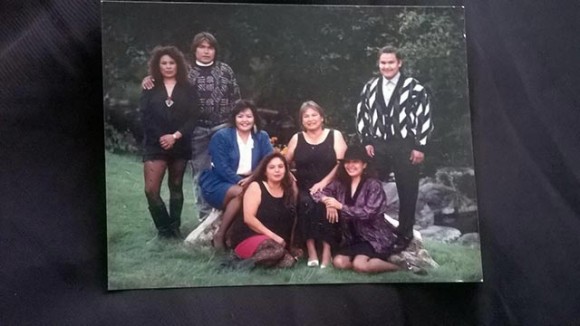

Photo 5: The Jack siblings and their mother. From left to right: standing: Lila, Leon, Leah (in chair), Mary (in chair, mother), Lonnie; sitting on grass: JoAnna, Lana. (Courtesy of Lana Jack)

3 Responses to “One Oregon Tribe’s Fight for Federal Recognition”

Articles On PRESS

PRESS:

- Jun 13 The Fight For Local Democracy in New York City

- May 25 Crown Heights Tenant Union: Building Power One Building at a Time in NYC

- May 25 Activists Occupy Shipping Container to Halt AIM Pipeline Construction in Upstate NY

- May 25 Barrington, NH votes 795 to 759 to Adopt Community Bill of Rights to Protect Waterways

- May 25 Revoking The Consent to be Governed

- Apr 25 Announcement of Nationally Coordinated Prisoner Workstoppage for Sept 9, 2016

- Apr 19 The Spirit of Occupy Lives on in France’s Emerging Direct Democracy Movement

- Apr 19 How Sanders Could Lay the Foundation for a Third US Political Party

- Apr 10 Some Possible Ideas for Going Forward

- Apr 7 Reclaiming Black Land in Grafton, New York

- Apr 7 Meet the Lead Organizer Behind the Upcoming Mass Sit-Ins to get Money out of Politics

- Mar 28 Dismantling Corporate Control Isn’t a Spectator Sport: An Interview With Thomas Linzey

- Mar 16 Preempting Trump: Barnstead, NH Adopts First-In-Nation Law Protecting Against Religious Persecution

- Mar 4 This New Era Of Unrest

- Mar 1 Washington State Supreme Court Guts Local Ballot Initiative Process

- Feb 9 Debating A ‘New’ Pan-European Anti-Austerity Movement

- Feb 9 How New York Stopped A Liquefied Natural Gas Project In Its Tracks

- Jan 28 Food, Land, and Freedom

- Jan 27 One Oregon Tribe’s Fight for Federal Recognition

- Jan 20 Worker, Civil and Environmental Rights as Legal Ends: Defying Commerce’s Logic

- Jan 20 Fast-Food Workers Plan Wave Of Strikes For 2016 Primaries

- Jan 18 Greece’s Varoufakis to Launch Pan-European Progressive Movement

- Jan 6 California’s Largest Tribe Passes First-In-Nation Enforceable Ban On GM-Salmon and GMOs

- Dec 29 The Leap Manifesto

- Dec 29 “People’s Injunction” Launched to Block Canadian Pipelines

- Dec 29 How Black Lives Matter Came Back Stronger After White Supremacist Attacks

- Dec 29 Can Local Law Enforcement Be Democratized By A People’s Movement?

- Dec 9 Preempting Democracy: What’s Not Being Voted on This November Is Sinister

- Dec 9 A Bill of Rights That Puts Workers Above Corporations

- Dec 9 Government and Gas Industry Team Up Against Local Fracking Ban Initiatives in Ohio

- Dec 9 Fighting Fossils, Letting Go of Regulatory Law

- Aug 26 In Colorado, A Revolutionary New Coalition Stands for Community Rights

- Aug 26 Climate Crisis Pits Local Governments Against 19th-Century Legal Doctrine

- Aug 26 Hundreds of Communities Are Building Legal Blockades to Fight Big Carbon

- Jul 21 Will Labor Go Local?

- Jul 20 Challenging Bedrock Law: “Dillon’s Rule” in Detroit and Beyond

- Jul 19 Defining a Federalist Approach to Immigration Reform

- Jul 18 Why Are Fracking Hopefuls Suing a County in New Mexico?

- Dec 8 Finally, The Court Case We’ve All Been Waiting For

- Nov 8 Ohio and Colorado Voters Adopt Community Bills of Rights

- Nov 8 Community Rights Organizer Sets Sights on Fracking in Southern Illinois

- Nov 8 Critical Issues Deserve a Higher Standard

- Nov 7 Indigenous Peoples Experience Of Climate Change And Efforts To Adapt (Video)

- Oct 8 Naomi Klein Addresses New ‘Mega Union’

- Oct 8 Disco may be the only way to stop Monsanto (Video)

- Oct 8 (Ohio) Frack-Backers Launch Preemptive Strikes against Democracy Attempt to Block Community Bills of Rights from Voters

- Oct 8 The California Domestic Workers Bill of Rights Speaks to the Need for Wise Immigration Reform

- Oct 8 Support Local Food Rights Will Not Be Deterred by Legislature’s Blow to Democracy

- Oct 8 Economic Sovereignty At Stake

- Oct 8 Sangerville, Maine Adopts Community Bill Of Rights Ordinance to Reject Transportation and Distribution Corridors

- Oct 8 Sacred Headwaters

- Oct 8 Oregon Communities Launch Statewide Network for Community Rights

- Sep 8 Bowling Green, OH Group Submits Bill of Rights Petition

- Sep 8 Judgment Day

- Sep 8 Judge Blocks Envision, SMAC Initiatives from Appearing on Ballot

- Sep 8 Why a Rights Based Ordinance In Nottingham, NH?

- Aug 8 What is the Local Food System Ordinance of Lane County?

- Aug 8 Lane County Initiative to Protect Local Farming Encounters Hurdle; Campaign Still Targeting May 2014 Election

- Aug 8 Benin: Local Knowledge And Adaptation To Climate Change In Ouémé Valley, Benin

- Aug 8 Local Food System Ordinance of Lane County, Oregon

- Jul 8 Envision Spokane Statement to Legal Action to Block the Community Bill of Rights from the Ballot

- Jul 8 Why does the Spokane City Council continue to ignore and distort the substance of the Spokane Community Bill of Rights?

- Jul 8 History of Efforts to Keep the Spokane Community Bill of Rights Initiative off the Ballot

- Jul 8 East Boulder County United Launches Campaign for the Lafayette Community Rights Act to Prohibit New Oil and Gas Extraction

- Jul 8 Benton County Community Group Files Petition for the Right to a Local, Sustainable Food System

- Jul 8 Rivers and Natural Ecosystems as Rights Bearing Subjects

- Jun 8 Caring for Home through Nature’s Rights

- Jun 8 From Field to Table: Rights for Workers in the Food Supply Chain

- Jun 8 Will Ohio Be Fracking’s Radioactive Dumping Ground?

- May 7 First County in U.S. Bans Fracking and all Hydrocarbon Extraction – Mora County, NM

- May 7 Self-Replication at Stake in Monsanto Patented Seed Case

- May 7 Guatemala: Mayan K’iché Environmental Sustainability As A Way Of Life

- May 7 Small Farms Fight Back: Food And Community Self-Governance

- May 7 State College Borough Gov Denies Pipeline Permit: Fight Isn’t Over

- May 7 Muzzling Scientists is an Assault on Democracy

- Apr 8 An Addition to the Climate Movement-Civil Disobedience Toolkit

- Apr 2 Thornton, New Hampshire Rejects Community Bill of Rights To Ban Land Acquisition for Unsustainable Energy Systems

- Apr 2 Grafton, New Hampshire Adopts Community Bill of Rights That Bans Land Acquisition for Unsustainable Energy Systems

- Apr 2 Highland Township Adopts Community Bill of Rights That Bans Toxic Injection Wells

- Apr 2 PSU Pipeline Violates Community Bill of Rights

- Jun 26 The United States Conference of Mayors Resolves that Corporations are not Natural Persons etc.

- Apr 30 Information and Documents concerning Oregon LNG

- Mar 9 1st Annual Read the Dirt Writing Competition!

- Feb 24 Oil Sands Pipelines, here?

- Feb 23 PRESS: Genetically Engineered Animals?

- Feb 23 PRESS: The 9th Annual Skagit Human Rights Festival March 2012

- Jan 27 Bellingham Rights-Based Ordinance Proposed to Stop Coal Trains

- Jan 26 PRESS: Occupy Seattle Joins in Solidarity with United Farm Workers

- Jan 20 Planning For a Future (Original)

- Jan 8 PRESS: Associated Students of Western Washington University Adopt Resolution Opposing Cherry Point Coal Terminal

by: Sean Aaron Cruzon: Wednesday 27th of January 2016

by: Sean Aaron Cruzon: Wednesday 27th of January 2016

by: Simonon: Thursday 28th of January 2016