Fighting Fossils, Letting Go of Regulatory Law

by: Simon Davis-Cohen Posted on: December 09, 2015

“For environmentalists to empathize and cooperate with social, racial, and economic justice activists — for a real climate movement to take root — they need to admit that the law is not on their side.”

Update: Since the original publication of this article, the “Coos County Right to Sustainable Energy Future Ordinance” has postponed its signature gathering and is now aiming to qualify for a 2016 ballot.

This piece originally appeared on earthisland.org/journal, in April 2015.

US fossil fuel exports are on the rise. The fall in global oil prices has bolstered already determined efforts to lift the 1975 ban on US crude oil exports. And as hydrofracking operations continue to expand, the industry is scrambling for regulatory approval to build a network of pipelines and terminals to transport natural gas around the country and worldwide.

Fossil fuel proponents jump through regulatory hoop after hoop, papers are pushed, and studies are conducted. Throughout this process, concerned citizens are assured by government agencies that projects will follow the law. They are told that if any endangered species habitat is destroyed, it will be preserved or created elsewhere. That any harm done by ripping pipeline through communities and wilderness, or planting a terminal in a fragile estuary, will be properly mitigated. Then, if all I’s are dotted and T’s crossed, permitting approval often follows. Final decisions over authorization generally take place behind closed doors.

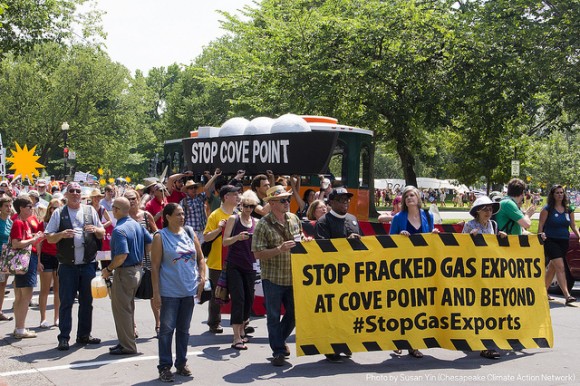

At Cove Point, Maryland, Jordan Cove, Oregon, and elsewhere, prospective exporters of domestic liquefied natural gas (LNG) have been wading through this process for years.

Activists opposing the terminals have jumped through the regulatory hoops, too. Writing public comments, projecting toxin levels, measuring harm — desperately appealing to language regulatory agencies can understand.

Despite tremendous public opposition and countless arguments to the contrary, last fall the Cove Point terminal expansion received Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approval. In Oregon’s Jordan Cove, FERC has given a tentative green light that is conditioned on the completion of other pending permit applications.

Jordan Cove activists are working tirelessly to stop the project. I spoke with one such activist, Jody McCaffree of Citizens Against LNG, an Oregon group opposing the Jordan Cove terminal through the regulatory process. She listed a slew of regulatory nightmares facing the terminal — its problematic proximity to an airport runway; the number of people who would receive second degree burns should a tanker explode; the terminal’s vulnerability to tsunamis; and the oyster farms that would be impacted, to name a few. Pointing to the egregious nature of the terminal, McCaffree expressed a faith that if enough public comments are filed, if the right lawyer is found, and if the regulatory process is honored by government agencies — in other words, if the law is followed — “[the terminal] will never get approved.”

Susan Jane Brown, an attorney with the Western Environmental Law Center who works with a diverse coalition of concerned property owners fighting the proposed pipeline that would feed the Jordan Cove terminal tells me, because of the numerous incomplete state and federal permits facing the terminal, “Don’t expect shovels to hit the dirt any time soon.” It could take years to get the permits FERC is waiting on. “A lot has to be done for this project to get approval, but anything is possible,” she says.

For McCaffree though, the possibility of approval is unfathomable. “FERC has a responsibility to protect the people and the environment,” she says. But, she adds, “FERC has not fulfilled its duties…. [The project] should have never made it this far…. The process needs to be challenged…. They are not doing the process the way it was designed.”

Regulatory agencies be damned

Amid disappointment in the official regulatory process, a non-regulatory, rights-based, campaign utilizing collective civil disobedience has emerged to block the Jordan Cove project in Coos County, OR.

To deny the terminal, Coos County citizens are working to pass “The Coos County Right to Sustainable Energy Future Ordinance.” The ordinance, billed as a “Community Bills of Rights,” targets the Jordan Cove terminal by banning transportation of fossil fuel into the county — with exceptions for local uses related to power, heating, and vehicle refueling — and by asserting the county’s right to self-governance. If passed, the law would effectively elevate the county’s community rights above any “rights” claimed by corporations proposing the terminal and state preempt that denies the county’s power to increase protections for health, safety and welfare, locally.

“We’ve done all the traditional things here,” says Mary Geddry, a leader of the Coos Commons Protection Council behind the Coos initiative. “I was just really frustrated with the whole regulatory thing…. I can’t even stomach attending [regulatory] meetings any longer because I feel like I’m giving credibility to a system that I feel is really illegitimate and has failed…. I was offended that we didn’t have any say really at the local level.”

According to Geddry, local volunteers have collected enough signatures to get the county rights ordinance on this fall’s ballot and will submit them at the appropriate time.

With this ordinance, Geddry’s group is working to flip the current relationship between local democratic majorities and private corporations. By denying corporations constitutional “rights” and elevating “community rights,” the initiative challenges long-standing legal structures that have shaped this country for centuries. “I see [the ordinance] as a peaceful revolution,” says Geddry. “I see it as a way to go forward to potentially solve many social ills, not just this particular project.” Passing this law could empower many different efforts to confront corporate “rights,” including anti-gentrification initiatives and anti-GMO campaigns, among others. A tall task for a small county on Oregon’s southern coast.

To help out, the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF), a non-profit that got its start opposing corporate farming in Pennsylvania, is offering pro bono legal council to defend Coos County’s law. CELDF has advised nearly 200 other US communities in passing similar anti-corporate, self-governance ordinances.

Coos County will not be the first county in Oregon to propose a rights-based measure challenging corporate rights. Benton County will vote on an anti-GMO ordinance this spring; last year Josephine County’s pesticide-focused initiative was defeated at the ballot after being vastly outspent by its opposition; and Lane County has been fighting pre-election challenge after challenge to get their anti-GMO bill on the ballot. And that’s not all. Together, these communities and others have formed the Oregon Community Rights Network (OCRN), also with support from CELDF, to propose a state constitutional amendment that would do for every Oregon community what the Community Bill of Rights ordinance would do for Coos: elevate local decision-making power above corporate “rights.” OCRN organizers have initiated efforts to put the amendment on the 2016 fall state ballot.

I ask McCaffree what she thinks about this approach. She is sympathetic: “People got frustrated because, just as I told you, [the regulatory agencies] ignored us.” She adds, “I support their efforts, but I’m too busy getting people involved with the permitting process.”

Clinging to the regulatory system

Those working within the regulatory system make important points. Many projects are denied permits due to regulatory shortcomings. However, under this system, there are always some projects that get approval, which is all the fossil fuel industry needs to continue business as usual. So although those working within the regulatory system win battles, they are losing the war.

Despite this, many still believe that the system has their best interests at heart. As McCaffree says, “I still believe that there is a system that was designed and it should be working.” Others would argue the opposite: That the system of law is working exactly as intended.

Environmentalists’ suspicions that the law may not serve their best interests have been bubbling for a time, and now, they’ve begun to boil. Mind you, for some, these suspicions have been boiling for a while. Just ask the hundreds of thousands of refugees annually detained or the millions of citizens put behind bars for committing non-violent offenses who must navigate a legal system that is often stacked against them.

For environmentalists to empathize and cooperate with social, racial, and economic justice activists — for a real climate movement to take root — they need to admit that the law is not on their side. And this is happening. As the regulatory process continues to be revealed for what it is — a process that allows destructive projects to proceed — we should expect to see more efforts like the Coos Community Bill of Rights that challenge corporate privilege and abandon regulatory law. What this means for environmental and social movements’ collaboration is yet unfolding.

In the meantime, those searching for a concrete political tactic to unite our at-times disparate movements might consider lawmaking that explicitly elevates local majorities above corporations’ whims.

Photo: by chesapeakeclimate, on Flickr

Articles On PRESS

PRESS:

- Jun 13 The Fight For Local Democracy in New York City

- May 25 Crown Heights Tenant Union: Building Power One Building at a Time in NYC

- May 25 Activists Occupy Shipping Container to Halt AIM Pipeline Construction in Upstate NY

- May 25 Barrington, NH votes 795 to 759 to Adopt Community Bill of Rights to Protect Waterways

- May 25 Revoking The Consent to be Governed

- Apr 25 Announcement of Nationally Coordinated Prisoner Workstoppage for Sept 9, 2016

- Apr 19 The Spirit of Occupy Lives on in France’s Emerging Direct Democracy Movement

- Apr 19 How Sanders Could Lay the Foundation for a Third US Political Party

- Apr 10 Some Possible Ideas for Going Forward

- Apr 7 Reclaiming Black Land in Grafton, New York

- Apr 7 Meet the Lead Organizer Behind the Upcoming Mass Sit-Ins to get Money out of Politics

- Mar 28 Dismantling Corporate Control Isn’t a Spectator Sport: An Interview With Thomas Linzey

- Mar 16 Preempting Trump: Barnstead, NH Adopts First-In-Nation Law Protecting Against Religious Persecution

- Mar 4 This New Era Of Unrest

- Mar 1 Washington State Supreme Court Guts Local Ballot Initiative Process

- Feb 9 Debating A ‘New’ Pan-European Anti-Austerity Movement

- Feb 9 How New York Stopped A Liquefied Natural Gas Project In Its Tracks

- Jan 28 Food, Land, and Freedom

- Jan 27 One Oregon Tribe’s Fight for Federal Recognition

- Jan 20 Worker, Civil and Environmental Rights as Legal Ends: Defying Commerce’s Logic

- Jan 20 Fast-Food Workers Plan Wave Of Strikes For 2016 Primaries

- Jan 18 Greece’s Varoufakis to Launch Pan-European Progressive Movement

- Jan 6 California’s Largest Tribe Passes First-In-Nation Enforceable Ban On GM-Salmon and GMOs

- Dec 29 The Leap Manifesto

- Dec 29 “People’s Injunction” Launched to Block Canadian Pipelines

- Dec 29 How Black Lives Matter Came Back Stronger After White Supremacist Attacks

- Dec 29 Can Local Law Enforcement Be Democratized By A People’s Movement?

- Dec 9 Preempting Democracy: What’s Not Being Voted on This November Is Sinister

- Dec 9 A Bill of Rights That Puts Workers Above Corporations

- Dec 9 Government and Gas Industry Team Up Against Local Fracking Ban Initiatives in Ohio

- Dec 9 Fighting Fossils, Letting Go of Regulatory Law

- Aug 26 In Colorado, A Revolutionary New Coalition Stands for Community Rights

- Aug 26 Climate Crisis Pits Local Governments Against 19th-Century Legal Doctrine

- Aug 26 Hundreds of Communities Are Building Legal Blockades to Fight Big Carbon

- Jul 21 Will Labor Go Local?

- Jul 20 Challenging Bedrock Law: “Dillon’s Rule” in Detroit and Beyond

- Jul 19 Defining a Federalist Approach to Immigration Reform

- Jul 18 Why Are Fracking Hopefuls Suing a County in New Mexico?

- Dec 8 Finally, The Court Case We’ve All Been Waiting For

- Nov 8 Ohio and Colorado Voters Adopt Community Bills of Rights

- Nov 8 Community Rights Organizer Sets Sights on Fracking in Southern Illinois

- Nov 8 Critical Issues Deserve a Higher Standard

- Nov 7 Indigenous Peoples Experience Of Climate Change And Efforts To Adapt (Video)

- Oct 8 Naomi Klein Addresses New ‘Mega Union’

- Oct 8 Disco may be the only way to stop Monsanto (Video)

- Oct 8 (Ohio) Frack-Backers Launch Preemptive Strikes against Democracy Attempt to Block Community Bills of Rights from Voters

- Oct 8 The California Domestic Workers Bill of Rights Speaks to the Need for Wise Immigration Reform

- Oct 8 Support Local Food Rights Will Not Be Deterred by Legislature’s Blow to Democracy

- Oct 8 Economic Sovereignty At Stake

- Oct 8 Sangerville, Maine Adopts Community Bill Of Rights Ordinance to Reject Transportation and Distribution Corridors

- Oct 8 Sacred Headwaters

- Oct 8 Oregon Communities Launch Statewide Network for Community Rights

- Sep 8 Bowling Green, OH Group Submits Bill of Rights Petition

- Sep 8 Judgment Day

- Sep 8 Judge Blocks Envision, SMAC Initiatives from Appearing on Ballot

- Sep 8 Why a Rights Based Ordinance In Nottingham, NH?

- Aug 8 What is the Local Food System Ordinance of Lane County?

- Aug 8 Lane County Initiative to Protect Local Farming Encounters Hurdle; Campaign Still Targeting May 2014 Election

- Aug 8 Benin: Local Knowledge And Adaptation To Climate Change In Ouémé Valley, Benin

- Aug 8 Local Food System Ordinance of Lane County, Oregon

- Jul 8 Envision Spokane Statement to Legal Action to Block the Community Bill of Rights from the Ballot

- Jul 8 Why does the Spokane City Council continue to ignore and distort the substance of the Spokane Community Bill of Rights?

- Jul 8 History of Efforts to Keep the Spokane Community Bill of Rights Initiative off the Ballot

- Jul 8 East Boulder County United Launches Campaign for the Lafayette Community Rights Act to Prohibit New Oil and Gas Extraction

- Jul 8 Benton County Community Group Files Petition for the Right to a Local, Sustainable Food System

- Jul 8 Rivers and Natural Ecosystems as Rights Bearing Subjects

- Jun 8 Caring for Home through Nature’s Rights

- Jun 8 From Field to Table: Rights for Workers in the Food Supply Chain

- Jun 8 Will Ohio Be Fracking’s Radioactive Dumping Ground?

- May 7 First County in U.S. Bans Fracking and all Hydrocarbon Extraction – Mora County, NM

- May 7 Self-Replication at Stake in Monsanto Patented Seed Case

- May 7 Guatemala: Mayan K’iché Environmental Sustainability As A Way Of Life

- May 7 Small Farms Fight Back: Food And Community Self-Governance

- May 7 State College Borough Gov Denies Pipeline Permit: Fight Isn’t Over

- May 7 Muzzling Scientists is an Assault on Democracy

- Apr 8 An Addition to the Climate Movement-Civil Disobedience Toolkit

- Apr 2 Thornton, New Hampshire Rejects Community Bill of Rights To Ban Land Acquisition for Unsustainable Energy Systems

- Apr 2 Grafton, New Hampshire Adopts Community Bill of Rights That Bans Land Acquisition for Unsustainable Energy Systems

- Apr 2 Highland Township Adopts Community Bill of Rights That Bans Toxic Injection Wells

- Apr 2 PSU Pipeline Violates Community Bill of Rights

- Jun 26 The United States Conference of Mayors Resolves that Corporations are not Natural Persons etc.

- Apr 30 Information and Documents concerning Oregon LNG

- Mar 9 1st Annual Read the Dirt Writing Competition!

- Feb 24 Oil Sands Pipelines, here?

- Feb 23 PRESS: Genetically Engineered Animals?

- Feb 23 PRESS: The 9th Annual Skagit Human Rights Festival March 2012

- Jan 27 Bellingham Rights-Based Ordinance Proposed to Stop Coal Trains

- Jan 26 PRESS: Occupy Seattle Joins in Solidarity with United Farm Workers

- Jan 20 Planning For a Future (Original)

- Jan 8 PRESS: Associated Students of Western Washington University Adopt Resolution Opposing Cherry Point Coal Terminal