Native Resilience and Interethnic Cooperation: How Natives are adapting to climate change, and helping their non-Native neighbors follow suit

by: Zoltan Grossman Posted on: August 08, 2013

Editor’s Note: Natives are used to challenges—colonization offers an example. Natives’ historic resiliency and local traditional knowledge, along with their political sovereignty, is empowering them to lead in the effort to adapt to today’s changing climate. Grossman offers a run-down of interethnic cooperation among Natives and non-Natives, from the Midwest to the Northwest. Have you heard of the Cowboy and Indian Alliance? It turns out that communities where conflict has historically been most intense are the places where cooperation more easily develops.

For more on Indigenous Climate Adaptation see the following reprints from Indigenous Peoples Issues and Resources:

– Bolivia: Building Resilience To Climate Change Through Indigenous Knowledge – The Case Of Bolivia (Read here)

– Benin: Local Knowledge And Adaptation To Climate Change In Ouémé Valley, Benin (Read here)

By Zoltán Grossman, Professor of Geography and Native Studies at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington

Simon Davis-Cohen: What is Native Resilience, how does it manifest, and where is it making progress today?

Zoltán Grossman: Indigenous peoples are on the front line of climate change. Native harvesters are usually the first to feel its effects, and Indigenous subsistence economies and cultures are the most vulnerable to climate catastrophes. In this view, the fate of Native peoples and their cultures are a “miner’s canary” that provides an early warning to the fate of all humanity. On the other hand, Indigenous peoples have certain advantages in responding to the challenge of climate change, compared to non-Native neighbors or local governments. Their continued lifeways (not their deaths) can provide some direction to the rest of humanity. Perhaps the “miner’s canary” story could be changed, so the canary escapes the cage, flaps its wings, and shows the hapless miner a safe way out of the toxic mine. Indigenous knowledge and experience has the potential to help the rest of humanity get more out of harm’s way.

Native peoples have faced massive ecological and economic changes in the past—from colonialism, genocide, epidemics, industrialization, and urbanization—yet many Native cultures have survived against overwhelming odds. The climate crisis is the latest (and perhaps the ultimate) challenge, but this history may make Native peoples better equipped than non-Native society that is completely reliant on chain grocery stores and shopping malls. Non-Native neighbors can even begin to look to Native nations for models to make their own communities more socially just, more ecologically resilient, and more hopeful.

Climate change discourse should not only warn Native communities of the dangers ahead, but empower them around inherent tribal strengths–such as Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Indigenous cultures have centuries of experience with local natural systems, so they can recognize environmental changes before Western scientists detect them and can develop ways to respond to these changes. Another strength is political sovereignty. Because tribes have a unique status as nations, they can develop their own models of dealing with climate change and managing nature in a sustainable way. Finally, in contrast to much of the non-Native population, Indigenous peoples retain a sense of community. Native peoples still have extended families that care for each other, assume responsibility for each other, and extend hospitality in times of need.

Mitigating climate change can also be used as a way to level the playing field between Native and non-Native communities. Around the country, tribes are beginning to tap into renewable energies, such as wind and solar. Here in Washington State, local tribal/non-tribal cooperation to restore salmon habitat provides a template for collaboration in response to climate change. The Tulalip Tribes, for example, are cooperating with dairy farmers to keep cattle waste out of the Snohomish watershed’s salmon streams by converting it into biogas energy. Farmers who had battled tribes now benefit from tribal sustainable practices. The anthology we recently edited at The Evergreen State College, Asserting Native Resilience, tells some of these stories of local and regional collaboration for resilience.

SDC: How can threats to regional and local resources bring once divided ethnicities together? Why is interethnic cooperation so valuable when protecting the places we live?

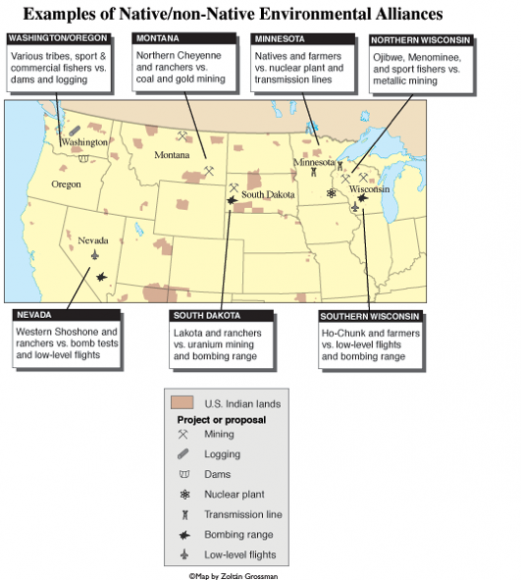

ZG: Since the 1970s, unlikely alliances have joined Native communities with their rural white neighbors (some of whom had been their worst enemies) to protect their common lands and waters, in states such as Washington, Oregon, Montana, Nevada, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. These unique convergences have confronted mines, dams, logging, power lines, nuclear waste, military projects, and other threats. In each of these cases, Native peoples and local white farmers, ranchers or fishers found common cause to defend their mutual place, and unexpectedly came together to protect their environment and economy from an outside threat, and a common enemy. They knew that if they continued to fight over resources, there may not be any left to fight over. Some rural whites who had been opposing Native rights began to see Native treaties and sovereignty as better protectors of common ground than their own local and state governments.

It would make logical sense that the greatest cooperation would develop in the areas with the least prior conflict. Yet a recurring irony is that cooperation more easily developed in areas where tribes had most strongly asserted their rights, and the white backlash had been the most intense. Treaty rights claims in the short run caused conflict, but in the long run educated whites about tribal cultures and legal powers, and strengthened the commitment of both communities to value the resources. A common sense of place extended beyond the immediate threat, and redefined their idea of home to include their neighbors.

In Washington State, the tribes emerged from the fishing wars of the 1960s and ‘70s with their treaties upheld in the federal courts, enabling them to use treaty rights as a legal tool to protect salmon habitat. The result was State-Tribal “co-management,” recognizing that the tribes have a seat at the table on natural resource issues outside the reservations. The Nisqually Tribe, for instance, is today recognized in its watershed as the lead entity in creating salmon habitat management plans for private farm owners, and state and federal agencies.

Before I moved to Washington eight years ago, I was active in Wisconsin supporting Native treaty rights. In the late 1980s, crowds of white sportsmen gathered to protest Ojibwe treaty rights to spear fish. Even as the racist harassment and violence raged, tribes presented their sovereignty as a legal obstacle to mining plans, and formed alliances such as the Midwest Treaty Network. Instead of continuing to argue over the fish, some white fishing groups began to cooperate with tribes to protect the fish, and won victories against the world’s largest mining companies. After witnessing the fishing war, seeing the 2003 defeat of the Crandon mine gave us some real hope. Now a decade later, the Bad River Ojibwe are leading the fight to stop iron mining, drawing on these past successes.

In the 2010s, new unlikely alliances of Native peoples and their rural white neighbors are standing strong against fossil fuel projects. In the Great Plains, grassroots coalitions of Native peoples and white ranchers and farmers (including the aptly named “Cowboy and Indian Alliance”) are blocking the Keystone XL oil pipeline and coal mining. In the Pacific Northwest and B.C., Native nations are using their treaties against plans for coal terminals and oil trains and pipelines, partly because shipping and burning fossil fuels threatens their fisheries. In New Brunswick, Mi’kmaq and Maliseet are confronting shale gas fracking, joined by non-Native neighbors. In this way, Native nations are leading the way not only in climate change adaptation, but also in mitigation—by keeping the fossil fuels in the ground. Slowing the growth of pipelines and rail networks can make a real difference, because shipping is the Achilles heel of the fossil fuel monster.

SDC: Why is climate adaptation a social issue of equity?

ZG: Climate change adaptation is usually presented as a sad or scary topic, but it can also be seen as an unprecedented opportunity. Adaptation can be used as a reason to quickly make fundamental changes in our environmental, economic and cultural practices that otherwise may take years to implement. Adaptation is a good excuse to make necessary changes that we should be making anyway for a healthier future, and making the changes more quickly than we otherwise would have. A sense of community and respect for the land are no longer just good ideas, but they are absolutely necessary to survive the troubles ahead.

Climate disasters are often used to divide communities, centralize political control, and privatize economies, as described in Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine. As a flip side of the shock doctrine, communities can use climate change adaptation to increase awareness of ecological ways to prevent future disasters, the need to share resources and deepen cooperation among neighboring communities–finding ways to institutionalize this collaboration beyond the immediate sandbagging of a river. In her book A Paradise Built in Hell, Rebecca Solnit describes how communities come together in the face of disaster, sometimes across racial lines. Some of the most important “green jobs” for youth may be in rural and urban planning, disaster prevention, and emergency response, not only to heal our communities but to make them more humane and sustainable than they were before the disasters.

Planning for disasters can also level the playing field between Native and non-Native communities. The Swinomish Tribe has taken the lead among Native nations by starting the Swinomish Climate Change Initiative, working closely with local non-Native governments in the Skagit River Delta (some of whom had actively opposed tribal fishing and water rights) to respond to coastal flooding and protect freshwater supplies from sea-level rise. The Initiative serves as a model for other tribes to account for climate change through joint planning with their neighbors. As another innovative example of planning ahead, the Nisqually Tribe signed an agreement with the City of Olympia to switch its drinking water from lowland springs to a well field on higher ground. The proactive move avoids possible saltwater intrusion from sea-level rise. The Quileute and Hoh tribes are now relocating housing and infrastructure to high ground, to avoid tsunamis, coastal flooding, and sea-level rise.

SDC: Do you believe local communities should have the right to self-govern their climate adaptation strategies? If so, what currently stands in the way of enjoying this right?

ZG: To some extent, local communities can already exercise zoning authority to make harmful projects more expensive, but rarely can they legally say ‘no’ to such a project. Since Native nations possess sovereignty that predates the United States, and treaty rights are constitutionally recognized as the “Supreme Law of the Land,” tribes more often have the ability to say ‘no.’ Environmental partnerships of tribal and local governments can be very powerful because tribes can bring in federal agencies, and local governments can provide legitimacy to the public. But many local governments are resentful of tribal jurisdiction, so they instead put obstacles in the way of tribal sovereignty, and end up hurting themselves. And some tribal governments, subject to economic pressures and desperate to generate jobs, are also attracted to corporate promises, sometimes over the objections of their own tribal members.

In situations of climate catastrophes, collaboration by tribal and local governments can prevent greater losses of life and community wealth. Many tribes now work with local governments on emergency services, such as fire trucks or sharing medical services. Deeper relationships will be needed in case of climate disasters. In responding to natural disasters, tribes can lead the way by being models to neighboring local governments. For example, during a tsunami warning eight years ago, Washington coastal tribes quickly evacuated their reservations, while non-Native citizens were angered that their own local governments did not respond as quickly. During windstorm blackouts and floods, some Washington tribes have opened their emergency shelters and health clinics to adjacent towns. Blizzards and ice storms also brought together tribal and local governments. When local communities get cut off from the rest of the region by a landslide, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is not going to ride in to rescue them. Tribes and their non-Native neighbors will have to rely on each other, whatever their histories of conflict.

However, tribal-local cooperation only works if local governments respect the inherent sovereignty of Indigenous nations and understand how tribal sovereignty can actually benefit them. By slowly turning local governments from adversaries into allies, tribal governments can strengthen their own sovereignty. Tribal nations are not just local stakeholders or another nonprofit organization endorsement to slap on a poster, or to open a conference with a colorful welcoming ceremony. They are governments with a nation-to-nation relationship to the federal government, and their status should be respected, with a seat at the decision-making table. Our responsibility as non-Native community organizers is not to dissect or appropriate Native cultures, or get involved in internal tribal politics, but to help remove the obstacles to tribal sovereignty in our own government and communities. As the Native comedian Charlie Hill says, “we have the answers to fix this country because we have the owner’s manual–and that’s not just a joke.”

Photo: Matt Lavin/Flickr

Articles On Ideas

Ideas: Lessons learned, perspectives, advice and more by and for organizers working toward a more democratic society.

- Sep 26 Education Sneak Peek

- Jun 5 US Climate Movement: Funnel Money Downward if You Want to Survive

- Jan 12 For Teachers and Citizens: How to Respond to Federal Immigration Raids

- Jan 5 How To Respond When Your (Local) Government Gets Sued By A Corporation

- Dec 8 Occupy’s Not So Invisible Work

- Dec 8 Getting Specific About What We Want

- Dec 8 National Sovereignty At Stake

- Dec 8 Lessons Learned By A Federal Enforcer

- Dec 8 Sacred Democracy-The Marriage of the Ethical and the Moral

- Dec 8 A Briefing On The State-Owned Bank of North Dakota

- Nov 8 Politicizing a Social Worker

- Nov 8 Sacred Democracy-Enlightenment and Democracy

- Oct 8 The People Know Best, Should We Listen?

- Oct 8 Sacred Democracy-Democracy: a Work in Progress

- Oct 8 Dispatches from Denmark-Ærø

- Oct 8 Protect The Local Initiative Process-Why Support WA Initiative 517

- Oct 8 Questions for a County Council Could-Be

- Sep 8 A Brief Chat about Workers’ Rights

- Sep 8 Sacred Democracy-Glimmers of Empathy in the Shadows of History

- Aug 8 Native Resilience and Interethnic Cooperation: How Natives are adapting to climate change, and helping their non-Native neighbors follow suit

- Aug 8 Imagining a New Society: Comparisons from Iceland

- Aug 8 Sacred Democracy-Rites of Nature

- Jul 8 Sacred Democracy-The Beatitudes of Fairness

- Jul 8 Speaking With a ‘Fractivist’: Data Acquisition to Federal Exemptions

- Jul 8 Selections from the Public News Service-July 2013 (Audio)

- Jul 8 How the Declaration of Independence got Hijacked

- Jun 10 A Bright Future: Creative, Passionate Students at Class Academy in Portland Participate in Read the Dirt Environmental Writing Contest

- Jun 8 (Audio): Read the Dirt’s Coverage of the 2013 Public Interest Environmental Law Conference

- Jun 8 Sacred Democracy-Living Democracy as Spiritual Practice (Or Vice Versa)

- May 8 Sacred Democracy-The Moral Blueprint

- May 8 Transforming Faith

- Feb 25 Park Rangers to the Rescue

- Feb 11 Washington’s Renewables: An Introduction

- Dec 12 Species Banks

- Nov 23 Our Slaves

- Nov 17 NW Coal Ports: Voice your concerns, voice them loud!

- Nov 13 Meditations on our Future

- Nov 4 Book: Ecoliterate: How Educators Are Cultivating Emotional, Social, and Ecological Intelligence

- Oct 14 Equity, Environmental Justice, and Industrial Pollution in Portland

- Oct 8 Cities advising Counties?

- Sep 12 Talking with Washington State Legislators-Stanford

- Aug 26 Talking with Washington State Legislators-Pollet

- Aug 21 Help! I’m being Climate Changed!

- Jul 14 Questionnaire for the authors of: THE GOLDILOCKS PLANET The 4 Billion Year Story of Earth’s Climate-Oxford University Press

- Jun 17 Can City Planning Make Us Cooler, Healthier and Friendlier?

- Jun 11 The Results-2012

- Mar 25 Making Clean Local Energy Accessible Now (Part 1)

- Mar 8 Our Right To Know

- Jan 18 PROTECT ONLINE FREEDOM—READ THE DIRT DEPENDS ON IT!

- Dec 23 Talking About Our Nuclear Hazard

- Oct 28 Why make Mt. St. Helens a National Park?

- Oct 20 The Story behind the Book, A Great Aridness: Climate Change and the Future of the American Southwest

- Jun 23 McKibben Comments on Expansion of Coal Exports at Cherry Point (Whatcom County)

- Apr 3 WASTED POWER

- Dec 20 Meet Some Environmental Consultants

- Dec 5 Using Dirt to Teach

- Oct 21 The We, The I and The Dirt

- Oct 21 Turning Pollution Into Energy

- Oct 21 Orange and Green

- Oct 21 Election 2010: Talk with a WA State Supreme Court Candidate (Wiggins)

- Oct 21 Election 2010: Talk with a WA State Supreme Court Candidate (Chief Justice Madsen)

- Oct 20 Our Dirty Web Designer (Video)